John Graham MLC

Address given at Dinner held at Carriageworks to mark the Centenary of the commencement of the Great Strike 2 August 2017

Welcome to this remarkable place – Eveleigh Carriageworks. At its height, with the ATP site next door, it was one of the largest industrial sites in the southern hemisphere.

If this incredible building was a cathedral, there would have been a line of tourists out the door each morning coming to see it. In a way, given its history, that’s how we should think of it, as a worker’s cathedral. Probably the largest worker’s cathedral in the southern hemisphere.

We could have done more, as a movement and as a government, to recognise that history. Labor’s annual conference on Sunday took steps to remedy that, when it called on a future Labor government to recognise the history of this place and to appropriately mark it in future.

I also want to acknowledge that we meet on Aboriginal land, in this important place, in Redfern & Eveleigh, and pay respect to elders past and present.

If the labour movement’s Trades Hall headquarters represented its head, this place was its heart. Down at Trades Hall they might have determined movement strategy, but movement sentiment was determined here, by thousands of skilled workers labouring side by side. So it was on the 2 August 1917.

Nearly 6,000 workers from Eveleigh and the Randwick tram yards led the strike. What would those workers from 100 years ago think, if they were here tonight? Surely they’d laugh, to find that their metal bashing workshop is now a theatre? Surely they’d smile, to know that tonight we’re here, in memory of their struggle?

Here to stay, and ready to carry on their fight.

Friends, this is a story of comradeship and hatred. Bitter hatred. It is a story of murder, and an unfinished quest for justice.

It is the story of a crushing loss, where we win in the end. It’s an important story for me, because reading about it as a teenager inspired me to work for the union movement.

This was a crushing loss. Australia’s biggest strike, one third of the state’s unionists took part. There was a tremendous sense of comradeship, of community, amongst those who took part.

There was also the bitterness of a dispute conducted in the depths of war. Eighteen months since Gallipoli. The worst of the Somme was yet to come. Chifley described “a legacy of bitterness and a trail of hate…” from this strike.

The comradeship and the hatred are best captured in my favourite, very small, part of this exhibition. You’ve all seen the lilywhite badges worn by the striking workers. Well I hope you’ve seen the government’s response! The ‘Loyal Workers Industrial Crisis’ medal. Struck in 1917, and issued to strike-breakers.

The curators, with a marvellous sense of understatement, record this:

“Wearers risked verbal or physical abuse. As a consequence the badges were unpopular, and were either discarded or hidden by their owners.”

I say understatement because: deadset. Can you imagine safely wearing one of these government issued baubles, these imitation awards, on the streets of Redfern or Darlington or Eveleigh after the strike, or for any of the decades to come? In my mind there’s no greater symbol of the passions this strike raised.

I’d like you to join me tonight in thanking Carriageworks and Lisa Havilah for putting on this fantastic exhibition.

Let me talk about a couple of the people involved in this dispute.

Bill McKell, Premier in 1941, represented many of the striking families as the member for Redfern.

Doc Evatt – represented the striking workers as a junior counsel.

Joe Cahill, Premier in 1952, was working at the Eveleigh railyards as a fitter. Cahill’s card was stamped “agitator”, and he later struggled to find work.

Eddie Ward, the firebrand of East Sydney, also worked at Eveleigh. He refused to sign the conditions to be reinstated, and was in and out of work for seven years.

Ben Chifley after the strike was re-employed, not as a driver, but as a fireman. In future it meant he would be firing up the train for men who had scabbed on the strike. He later said this, “All that that harsh and oppressive treatment did as far as I was concerned was to transform me, with the assistance of my colleagues, from an ordinary engine-driver into the Prime Minister of this country.”

Finally Jack Lang, Premier in 1925, who legislated to restore the strikers’ privileges and seniority.

This crushing loss produced leaders for decades to come.

The government didn’t just hand out medals during this dispute. Their policy was to enlist strike-breakers, and issue some of them with revolvers.

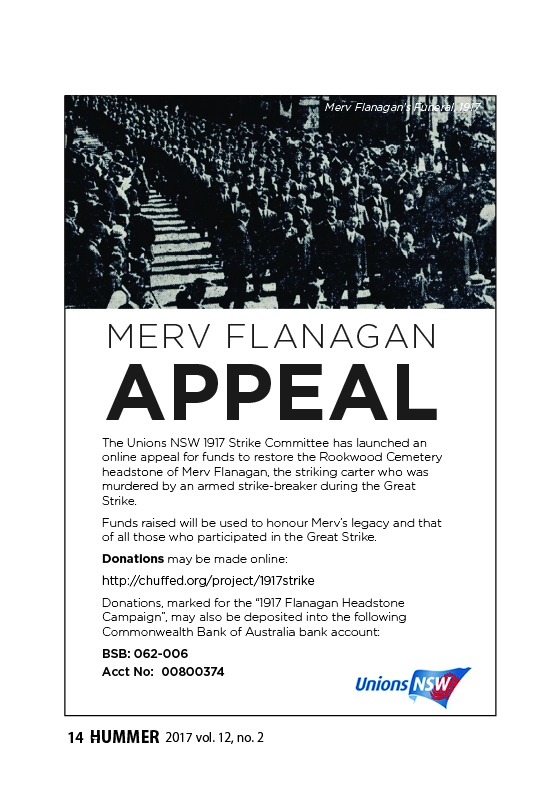

Tonight, we remember one person specifically. A labour movement martyr, murdered in this dispute. Merv Flanagan was a striking carter. His family are here with us tonight. On August 30 1917, there was an argument, a scuffle, and Merv Flanangan was shot dead on Bridge Road, Camperdown. He was with his brother James Flanagan, and his friend Henry Williams, also shot in the leg.

The man who fired the shots was Reginald Wearne. He was a strike-breaker from Bingara. He was the brother of a powerful conservative state politician.

What happened was tragic. What followed was an outrage.

Sydney’s establishment rallied around the murderer.

Wearne was quickly granted bail. He received hundreds of letters and telegrams of support, some of which described Flanagan as ‘an enemy of the state’ and ‘a parasite of the lowest social order.’ His defence was funded by the wealthy, including A. M. Hemsley of the law firm Allen, Allen and Hemsley who put the hat around at Sydney’s elite Union Club. Then Wearne was set free.

A Coroner’s inquest finding was used to have the manslaughter charges he faced, withdrawn. The Acting Coroner hailed from his home town of Bingara. By contrast, brother James Flanagan and Williams were jailed for 3 months each.

The murderer Wearne free.

James Flanagan and Williams jailed.

The striker Merv Flanagan dead.

100 years later, it is still an injustice.

Together tonight we agree to tell Merv Flanagan’s story. Together tonight, we join the call for the labour movement and the City of Sydney to permanently recognise the site of Merv Flanagan’s death in Camperdown.

Tonight Merv Flanagan lies buried in the Roman Catholic section of Rookwood cemetery. His grave is poorly marked. We need to fix that. Together tonight we launch a campaign to raise funds to change that…

…to tell his story…

…to mark his death…

…and to mark his grave.

Friends, this was a crushing loss. On this occasion the workers, united, were catastrophically defeated. But the workers, defeated, chose to fight, to organise industrially and politically. With leaders who knew the stakes. Their politics fired in the furnace of this dispute.

Leaders who went on to restore the seniority and rights of the strikers, to build a fair industrial relations system, and to build the Australian welfare state.

I think we can honestly say, looking back, that we won in the end. We also have to honestly say, that win came at a terrible cost. No one bore a greater cost than Merv Flanagan and his family.

Tonight we remember Merv Flanagan. We remember this struggle. We remember this lesson from 100 years ago:

We won’t always win…

But if you listen to Sally McManus… And when you listen to Mark Morey… And you get a sense around the movement at the moment, that we finally know this lesson again…

That when we choose to fight, we can win in the end.

John Graham continues to fight for justice for Merv Flanagan’s family. His condolence motion to the Flanagan family was passed by the NSW Upper House on November 2017. He is calling on the NSW Government to formally apologise and also to release any documents, including Cabinet documents and files, “on the incident, the legal process and the policy of issuing weapons to strike-breakers”.

Graham is also in discussion with the City of Sydney Council seeking to mark the site of Flanagan’s death on Bridge Road, Camperdown.