Rodney Cavalier

Address given at the Great Strike 1917 Gala Dinner,Goulburn Workers Club , 26 August 2017

NSW Railways were under the control of commissioners from their beginnings until 1932. The post of Chief Commissioner was one of the most powerful positions in Australian public life.

During the Great War 1914-18, before air travel, when mechanised road transport was in its infancy, railways were pre-eminent.

In July 1917, in an already combustible industrial relations climate, the Chief Commissioner introduced a regime of time cards that workers had to complete. Not completing was not an option.

The Commissioner was captured by time and motion studies then the vogue in the United States, an expression of the mantra that management is a science capable of study and productivity is the result of measurable burdens.

Time cards were supposed to measure the productivity of each employee. For employees it was another assault on their working conditions, a measure offensive to their dignity. Unions gave the commissioners fair warning that their members would not participate in the time card system. The commissioners were determined to proceed.

On 2 August 1917 employees at the Eveleigh Railway Workshop and the Randwick Tramways Workshop walked off the job. We are talking big numbers – 3000 at Eveleigh, 1300 at Randwick.

250 railway employees at Bathurst and 400 here at Goulburn went out of the instant. 14 unions were involved.

Revulsion at the indignity of the cards was the trigger for concerted action.

The extreme act of striking does not just happen. These men walked off the job because Australian politics had become poisonous. Respect for authority was at a low ebb. The NSW government wanted their rail employees to go on strike. The government wanted a reckoning.

Because many of us here lived through 1975 we think of it as our most dangerous constitutional crisis. That is not so. Conscription 1916-17 was far more dangerous. The events surrounding the Great Strike illustrate a nation dangerously divided against itself.

Men in the tens of thousands were dying in foreign fields in France and Belgium and in the deserts of the Middle East, they were perishing when their ships were sunk, expiring in fearful pain in hospitals near battle and hospitals in the tranquillity of England. Many more Australians, many many more, had been wounded. So many of the wounded suffered life-disabling inflictions. Minds and self-confidence were permanent casualties.

The streets of Goulburn contained shattered men moving around with limbs missing and men seemingly intact not making sense. So many women and children had lost husbands and fathers. Mothers and fathers had lost sons and brothers.

The Prime Minister, William Morris Hughes, one of the earliest of Labor Party activists, founder of two unions, had become duchessed on a visit to the Western Front that voluntary recruiting was insufficient to meet its obligations to the empire.

Hughes returned with a commitment to conscription. He well knew the ranks of his party were overwhelmingly in opposition. Unions were unanimously opposed. Hughes persisted. His solution was a plebiscite that would enable the electors of Australia to override the intransigence of his party, his caucus and his cabinet.

The plebiscite was more bitter, more personally vicious, than any referendum or state or federal election since.

The most solid opposition to conscription came from the members of Hughes’s own party. Members of caucus and ministers in his cabinet were trenchant in their opposition. In spite of assurances that debate would be free, Hughes sought to silence his opponents, a daring step given that meant silencing his cabinet and caucus colleagues.

The Hughes Labor government fell when cabinet processes ceased to work. Hughes was wont to boast – “With a fountain pen and Sir Robert Garran beside me I can rule the Commonwealth”. Sir Robert was the Federation’s first public service appointment, an appointment made on 1 January 1901. He was head of the Attorney-General’s Department.

Hughes made a fair fist of proving his boast. Neither cabinet nor Labor caucus was going to stand in his way.

The War Precautions Act was a severe measure designed to prevent seditious talk in support of the enemy. With Hughes and zealots, it became an instrument to silence critics of compulsory service. The trigger for the split in the Hughes government was an attempt to promulgate regulations under the Act. Presented to Cabinet, the regulations were rejected.

Hughes convened an Executive Council consisting of the Governor-General, a tame minister and himself, a quorum according to law. The Executive Council passed the regulations. His Excellency signed them. His signature made them law.

Think about that. Not before, not since, has an executive council made laws without cabinet authority. This was a constitutional revolution with the representative of the Crown at its centre. That would not be the last time the Crown stepped outside its proper vice-regal role.

Much of the Labor cabinet resigned. Hughes was expelled by his local branch, his federal electorate council, the NSW ALP and the two unions he played a role in founding. Labor suffered the most grievous split in its history.

On 28 October 1916 NSW voted no. Australia voted no. Goulburn voted no.

Hughes sought recovery from such a big defeat on the south coast. His rail journey to the meeting of caucus at Parliament House, Melbourne, began at Moss Vale. He travelled through this town in the carriage set aside for the prime minister. This journey was his last as a Labor leader.

At the final fateful meeting of caucus over which he presided, though expelled, no one challenged his right to take the chair. When a solid majority of caucus had declared itself against him, Hughes walked out of the room. No vote had been necessary. He was walking away from the party he had once loved, the party which had made him high and mighty. He did not return.

Across Australia the party split. In Ireland there is the Easter Uprising. There will be civil war. Russia has a revolution. Australia is a nation divided. Every Australian supports the troops. But a great many Australians have ceased to support the war. Personal losses have been so very great. The grief does not ever subside.

“Lest we forget” was not a challenge for a generation of Australians. The challenge was to find the space somewhere in their waking moments when they did not remember who had not returned.

Consider the circumstances of July 1917. Consider why the Railway Commissioners were emboldened to issue time cards and to insist on their completion. The Commissioners knew they enjoyed the full-blooded support of a coalition government calling itself Nationalist, a cabinet consisting of Tories and former Labor MPs expelled for their support of conscription.

The government is headed by a Labor rat in William Holman, a cabinet that is one-half former Labor ministers. Poachers have become game-keepers who reckon they know more than a little about the officials of the Railways union and how to defeat them.

The cabinet was spoiling for a fight. The Labor Party was the blood enemy. Leaders of unions had captured the Labor Party, debauched the party, turned its ranks against the Empire and the war, expelled them and defeated the conscription plebiscite.

Now, less than a year later, they were going to smash the unions.

The union movement was not averse to a showdown. Why would the union movement in NSW cop an assertion of authority by those in charge of the governments of NSW and Australia, once allies, once friends, who had behaved in so scurvy a fashion?

Real wages in Australia fell some 30 per cent 1914-19. Sacrifice seemed unequal. A wave of industrial action began in early 1916.

The unions sought an inquiry. They sought arbitration. The NSW government said no to every effort at compromise. The Holman government wanted the fight.

The narrative of the dispute is told so very well in a commemorative booklet written by Lucy Taksa and published by Unions NSW. The Great Strike has been examined by official inquiries at the time and in academic writings in recent decades.

Being here in Goulburn this night, I will try to examine what happened in this town.

We know that locomotive journeys out of Central before the strike were 660 per day. The strike cut the number to 74. That is a major reduction in economic activity.

Denied the living memories of participants, we are reliant on records of memory and the reportage of the Goulburn Evening Penny Post. Though coverage is heavily biased against the strikers, the Post is invaluable. The Post did seek to cover the story.

I am able to recite stories in the Post because of the mighty labours of Margaret Kearns. Margaret downloaded a suite of stories that looks complete and preserved them in chronological order. I know how time consuming that task was. The clippings have brought to life the strike in Goulburn. If my talk this night works it is because of Margaret.

I am no less indebted to Anna Wurth for the invitation and to Greg Price who ferried so much material to me and kept me informed of your plans for this night. Goulburn owes the commemorative committee so much.

Coverage in the Post is thorough. Each day there is the template – “Goulburn and the Strike”. Columns of text concentrate on the heroic efforts of the NSW Government to keep the trains running. It reports the arrival of trains and the successes of volunteers and staff reassigned to get the trains away.

Prose cannot disguise the absence of labour is playing havoc with the rail network in both directions. Passengers are wary to travel. The arrival of a loco does not mean it will be unloaded. If it is unloaded, there is no certainty the goods will be driven away.

Pickets are on both sides of the line. The pickets demand explanation from anyone passing through. The Post was sweating on violence. It did not come to pass. The worst the paper can report is bad language that may or may not have occurred.

Newspapers cease arriving.

Locomotives delivered mail from all parts of NSW to all parts of NSW. There was no alternative. Mechanised lorries are in their infancy. Without mail, commerce is disrupted, bills do not arrive, payments are not received.

The ranks of Goulburn’s rail workers are for the strike. The permanent way staff are unanimous. Engine drivers and firemen are not : 32 drivers and 16 firemen are available for work. The guards vote to remain at work but many guards walk out anyway. Clerks volunteer to shovel coal and ash. Some 20 Goulburn High students volunteer and are employed as cleaners.

Goulburn is a centre of militancy. Junee has stayed in. A lack of reports on Moss Vale suggests it was not involved. Goulburn is, of course, the most important rail centre on the Southern Line.

The strike in Sydney has occasioned a massive response. Sad to say the Sydney Cricket Ground was a camp for strike breakers and a depot for materials to break the strike. A big bus from Kenmore goes to Sydney in support of the non-strikers who are wearing the label of “loyalist”. Warders from Goulburn Gaol are enlisted as special constables for duty in Sydney. One can readily imagine how they dealt with strikers. Note that authority dared not turn them loose in their home town.

All up, some 1000 from the Southern Line have volunteered for Sydney. The Holman government has concentrated its efforts on breaking the strike in Sydney. Once broken at the centre, the government calculates, the holdouts in Goulburn and Bathurst will not be able to continue.

Those unintimidated are called “lily-whites” in honour of their refusal to buckle. Goulburn has a great many entitled to wear the badge made to honour them.

Word about other rail centres is mixed. Cootamundra is more than half out. Holman has cause to be anxious about Coota – he is the local MP. He won it as a Labor man. Can he hold it? He cannot.

The government has not moved one inch. It has set a date for a return to work. Anyone not back will be dismissed as and from midnight of that date. Goulburn Council declines an invitation from neighbouring councils to participate in strike breaking.

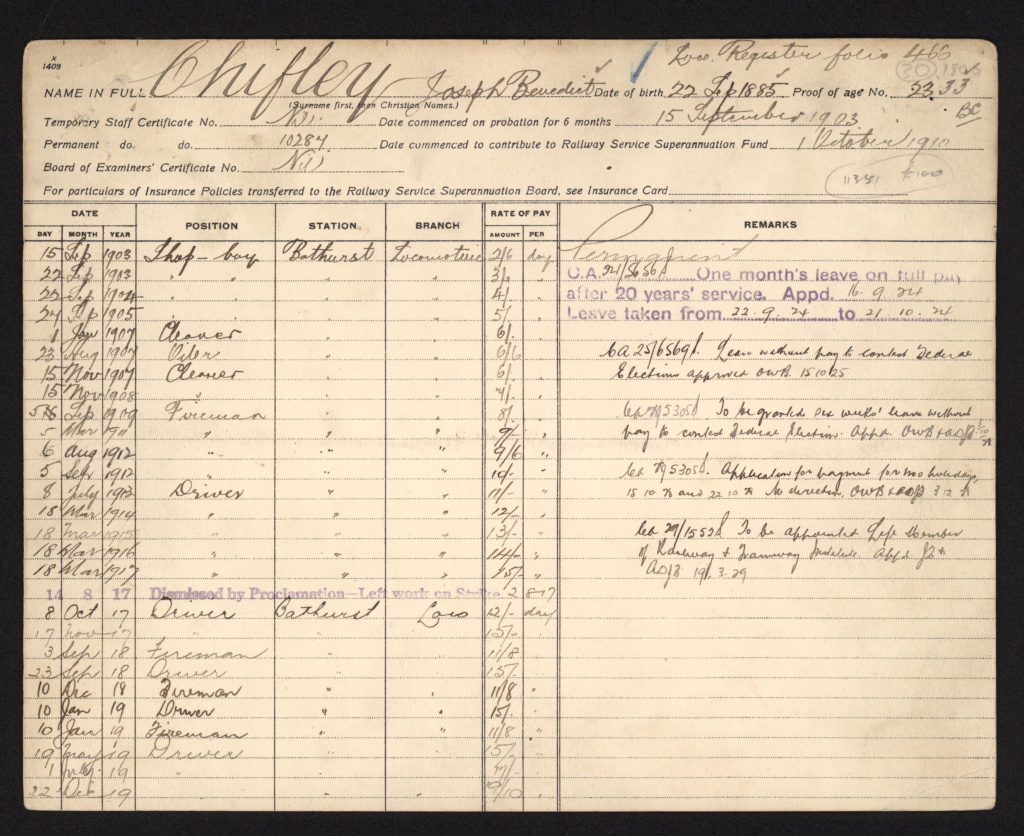

Dismissal notices are issued. Employment records receive precise annotation that indicates if the dismissed was an agitator. Dismissal means the loss of seniority, the loss of superannuation and any rights the government can withhold.

The government does not want the dismissed back. The Commissioners issue a statement that no striker is to be re-employed except with “the special permission of the Chief Commissioner”.

The Goulburn Defence Committee is relying on word from the central committee based in Sydney.

By the end of August the Post has a triumphant tone. Strikers are returning. They mean Sydney. Not Goulburn. On the previous Sunday a meeting at the Majestic Theatre voted unanimously to stay out.

For the government, country towns holding out is a sideshow. Volunteers, with their names reported, are being transported from Goulburn by car to Sydney. The need for a motor car reveals that the strikers continued to control rail movements in and out of Goulburn.

The town is divided. Sentiment is with the strikers. Will pubs serve the strike breakers? It appears that many will not.

The jobs of the strikers are being filled by new recruits. The Post exults that the strikers have passed the point of no return.

In Goulburn and across the bush the strikers avoid restlessness with useful tasks like rabbit shooting and cutting wood. The men carted it to people who could not afford to buy it. There is a telling note: “Business people are assisting in the way of supplying ammunition”.

We must not assume that the owners of capital in Goulburn were hostile to the strikers. General support from much of the town may explain local solidarity long after resistance in Sydney collapsed.

By 10 September the Sydney Committee is accepting terms of unconditional surrender. Trains are moving as before. The engine drivers and boilermakers have held out. On 19 September they vote to return.

But to what? The strikers have lost their jobs. 2000 railwaymen will not get their jobs back.

Joseph Benedict Chifley, engine driver from Bathurst, is compelled to write an appeal against his permanent exclusion. Only that he was among the very best of drivers is he allowed back. His seniority is forfeited. He has been busted to fireman working under engine drivers he once taught.

The strike was defeated by a united front of government and employers that evoked memories of the actions of government and employers to defeat the strikes of the early 1890s, a momentous defeat that inspired the founding of a Labor Party to advance the interests of workers and their families.

The government arrested strike leaders. By 30 August, 22 unions had been deregistered.

The government made hunger serve their cause: benevolent societies were instructed not to offer food or relief to the families of strikers. Families have suffered grievously. A feature has been the solidarity of women.

The strike had become total war.

If you were a worker on wages, if you were part of a working family, if you had joined your local Labour League in the flush of belief that you were transforming society, if you had family members who had gone to the Front or were sailing on ships, you felt you were under sustained attack. You had good cause to feel that way.

The defeat of the Great Strike emboldened WM Hughes to hold a second plebiscite on conscription. The Labor Party is irredeemably split, the unions are crushed. This time he will surely prevail. He misread Australia. The second plebiscite in December 1917 went down by a bigger margin than the first.

Commemoration of the Great Strike is an honourable recall of what should not ever be forgotten.

Unions did renew. Unions did regenerate. At the end of the strike, locomotive engine drivers confronted a union deregistered and the prospect of membership of a union favourably disposed to the Commissioners. Workers had to rebuild from the ruins: in 1922, of 3700 engine drivers, only 600 belonged to the union. Intense organisational work lifted that number to 2670 inside a year.

In 1925 the Lang government legislated to restore seniority as it was before August 1917.

Looking back from 30 years on when he was our Prime Minister, Ben Chifley reflected:

I should not be a Member of this Parliament today if some tolerance had been extended to the men who took part in the strike of 1917. All that harsh and oppressive treatment did as far as I was concerned was to transform me, with the assistance of my colleagues, from an ordinary engine-driver into the Prime Minister of this country.