In a TUTA Training Room

Michael Newman

What do we mean by trade union training? What is taught? What methods are used? What are the participants like? What are the trainers like? Rather than search for a definition, I want to describe how a union trainer might conduct a number of sessions dealing with negotiation. These sessions come from a course for workplace representatives run at the Sydney centre of the Australian Trade Union Training Authority (TUTA) in the mid-1980s. Participants for the course are drawn from a number of different unions and variously described as job reps, site reps, office reps or shop stewards. There are 24 of them in the training room.

The course is a four-day second-level course, meaning that the participants have already received some training in negotiation skills, and so the trainer starts out by asking participants to work in pairs and to share stories of their own experience of negotiating since they attended their first-level course. During this exercise there is likely to be a lot of noise in the training room, and occasional bursts of laughter. “Who had a total success,” the trainer asks. “And you don’t have to answer this, but did anyone have a total failure?” The trainer uses the stories told to review some of the theory and record it on the white board.

The trainer then runs a short trigger film showing a workplace representative in negotiation with a manager and asks the participants to work in groups of four or five to critique the rep’s performance. The critiques are shared. Disagreements may emerge between the groups, and between individual participants. Some of these differences will come about because of different practices in unions and different responsibilities given by unions to their workplace representatives. Other differences might come about because of the different political colours of the different unions. The trainer may let this discussion run for a few minutes in the belief that it is better to have any major differences put on the table.

In the final part of this session the trainer draws together the various critiques of the video and, with the help of the group, revises the steps involved in preparing for, engaging in, and following up a negotiation. The trainer ends the session by announcing that the remaining three sessions of the day – four and a half hours in all –will be spent on a negotiation exercise. The group goes to coffee break, usually a little subdued. Role-plays and simulations can be daunting prospects.

The Exercise

Back from the coffee break, the trainer divides the group into two teams, and distributes the instruction sheets that carry the scenario for the exercise. One group will play management and the other the union representatives. The trainer explains that there will be a second exercise in two days’ time and the roles will be reversed.

Immediately the mood changes. Even before all the instruction sheets are distributed people begin taking up positions. Half-jocular challenges are made. Half-cheerful insults traded. There is a sense of anticipation. It might be at this moment that the trainer chooses to lay down some ground rules. This exercise is to practice the skills and apply the theory examined in the last session. The teams can use any of the strategies identified and discussed, but they are not to play silly buggers. No getting up during the negotiation and standing menacingly behind the other team, for example. This instruction is directed at two hard rock miners from Cobar. No sudden unilateral changes to the scenario. This is directed at a rep from a public service union, who the trainer remembers from a level-one course and who is a factional warrior from the far left of the Australian Labor Party.

The teams go to separate syndicate rooms and are given an hour and a half to analyse the problems that have led to the dispute, prepare their cases, allocate roles to each of their team members, discuss strategies, and attempt to anticipate the other team’s case. The trainer keeps an eye on the groups but normally would not intervene beyond reminding them of the time.

Following another break, the two teams meet back in the main training room to conduct the negotiation. Often there is an awkward moment as they settle into position on opposite sides of the negotiating table. Once settled, they begin to negotiate. Including adjournments, the negotiation may take up to two hours to complete.

Normally the start is hesitant as each side tries to get the other side talking first, but as people become involved, the pace quickens, tension builds and the exercise takes on a dynamic of its own. In almost any negotiation exercise there are moments of frustration, disappointment, anger, excitement and elation. Under pressure, teams can come unstuck and begin arguing amongst themselves. Often when this happens they patch up their teamwork during an adjournment and come back into the negotiation with a new sense of purpose. Often all the time allocated for the exercise is needed and, when the trainer intervenes to announce that time is running out, the last few minutes are spent in a fury of bargaining. Usually some kind of agreement is achieved as a result of intense eyeball-to-eyeball negotiation right up to the deadline. When the exercise is over, people push back their chairs with relief, amazed at how involved they had become.

The Review

Now the trainer has to debrief the group and the exercise.

The trainer asks the participants to move the tables and chairs back into the U shape they were using in the previous training sessions. Always there is noise and banter as they do this: laughter, recriminations, claims and counter claims of victory, admissions of blunders. Some participants remain standing, pointing, talking loudly over others. Gradually people resume their seats. By returning to the positions they occupied before the exercise, the teams are broken up. Now people are seated but still talking excitedly across the U, reliving parts of the exercise, making comments and asking questions like: ‘Were you really going to close the place down?’; ‘We didn’t know he had gambling debts’; ‘Was that really your bottom line?’.

The trainer lets the discussion run on, but begins to intervene to let the less raucous have a say. Gradually, as the excitement dies down, the trainer intervenes more, first to examine the process. Was the preparation sufficient? No, people will often say, we needed twice the time. With the wisdom of hindsight, can each team say they predicted what the other team’s demands would be? Were they satisfied with the arguments they had prepared? Did they have demands, targets and bottom-lines all worked out? Did they organise their team before they went into the negotiation? Did they use adjournments? How did they use them?

Now the actual negotiation itself. Were they able to get the other side talking, and were they able to listen? Did the negotiation pass through any stages? Here the trainer begins asserting more control by using the whiteboard to outline the stages many negotiations go through. Was there a stage when both teams stopped thumping the table and began seeking possible areas of cooperation? How did they do this? Did they give anything away while they probed the other team? Which team moved into this final phase first? Was it to their advantage to do this?

Now to the substance of the negotiation. What was it all about? What were the two parties’ common interests? What were their conflicting interests? Here the trainer might take control of the session and deliver a mini-lecture of four or five minutes. Both union and management have a common interest in production. Production means survival for both. Both teams had a lot to lose if they could not reach agreement. But while unions and management may have a common interest in production, they have conflicting interests over the share of that production. The unions want their share in the form of increased wages, better working conditions, better super, less stress, more interesting work and a better social wage, while management wants to get hold of as much production as possible in the form of profit. Is that right? Is that analysis too simple? Were those conflicting and common interests there in the negotiation exercise?

The Result

Finally the trainer addresses the question of the result.

Which team won? In response to this question both teams may vociferously claim victory. But, says the trainer, negotiation is not like a tennis match. There are no points and there is no umpire. If we become obsessed with scoring off the other side, we can easily lose sight of the substance of the negotiation. We might come out thinking we won, only to realise that while we were scoring all the fancy points the other side had been quietly working away at getting what they wanted.

So perhaps we should not evaluate a negotiation by asking who won. Perhaps we should ask: Did we solve the problem? After all, we came to the negotiation table because each side had a problem. Did each team effectively solve their particular problem? There can be some lively discussion in response to this with members of the same team not always in agreement. But, asks the trainer, if both sides set out to solve their problems, why could they not consult rather than negotiate?

Often the replies to this are: we might get sidetracked and end up solving the boss’s problems; or, why should we do management’s work for them? Here there might be a discussion of those areas of common interest where consultation rather than negotiation may be possible, but the trainer must draw the session to a close, and so asks again: what question should participants use to evaluate a negotiation? ‘Did we win?’ will not do. ‘Did we solve our problem?’ is all right but there are traps in it.

What the trainer is hoping to draw from the group and what, in any event, the trainer writes on the whiteboard in order to provoke the final moments of reflection is a question crucial to the evaluation of any union activity:

Did we make a gain for our members?

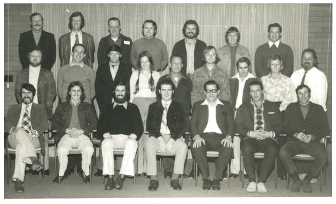

Back row: Tony Kibblewhite (DLI trainer), John Rudolph (DLI trainer), ?, Kevin Davern (AIEU SA), ?, ?, Graeme Cairns (TUTA Centre Tas).

Middle row: Michael Beahan (Interim C’tee and WA), ?,

Wendy Davern/Townshend (Vic), ?, Frank Doyle (?), ?, ?,

Barbara, (Clyde Cameron College admin staff), ?.

Seated: Mike Burton, ?, ?, Jim McKiernan (Education Officer, AMWSU WA), ?, ?, Sean Kelly (Tas Interim C’tee Director).

Photo courtesy Michael Beahan.

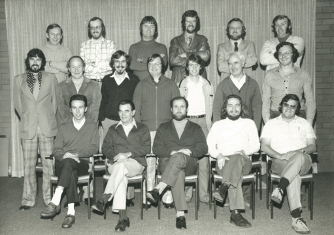

Back row: Ken Ahearn (AMWSU WA, Interim C’tee trainer), Geoff Farey (TUTA Centre Vic and Interim C’tee trainer), ?, John Rudolph (DLI trainer), Michael Beahan (Interim C’tee and WA), Max Ogden (Education Officer, AMWSU, Vic). 6

Middle row: Warwick McDonald (Interim C’tee trainer), Vic TU, ?, ACOA Vic, ?, Jim Davis (TWU Vic), Michael Johnston (TUTA Centre NSW and Interim C’tee trainer). 5 ???

Seated: Peter Collins, John Sandilands (? VBEF, SA), ?, Bob Richardson (Education Officer, AMWSU, NSW and Interim C’tee trainer), Alan Evans (?, Interim C’tee trainer).4 ??

Photo courtesy Michael Beahan