Michael Quinlan, Lynda Matthews and Philip Bohle

On the 23rd of March 1887 a violent methane explosion at the Bulli Colliery killed 81 men and boys, one of the worst mine disasters in Australian history. Fifty women lost their husbands, 80 children lost their fathers and 14 of the boys who died were under 18 years of age, some well under. Families were devastated and, in several instances, families were almost entirely destroyed. Amongst those killed were William Bouren/Bourne and his three sons Felix, William and James. Thomas Harris and his two sons, Thomas Jnr and Francis, also died. Reaching the site one woman was reputedly heard to exclaim ‘oh my boys, my beautiful, beautiful boys’.[1] Similar statements continue to be made by those losing a family member to traumatic workplace death, such as that of miner Michael Welsh’s daughter in the title of this paper.[2]

Words can barely do justice to the grief and harm inflicted by the Bulli disaster. There was no workers’ compensation or widow’s pension to deal with the financial effects which were, and can still be, generational. A government replete with coalmining interests ordered a Royal Commission which, in typical fashion, apportioned some blame to work practices without considering the context of power relations and reward systems at the mine (in contrast to the more recent Pike River mine disaster Royal Commission). Its recommendations for improved regulation failed to address key issues, and despite some improvements, it wasn’t until 100 years later that NSW achieved relatively effective mine safety legislation. In 1876, NSW coalminers had secured legislative rights to appoint their own check inspectors to safeguard their health and safety – only the second jurisdiction in the world to do so – but in the Bulli region this system was under-developed in 1887 due to employer intimidation of those appointed. Through union struggle, the system grew and became more effective, and check inspectors have continued to play an active role in investigations, commissions and royal commissions – aiding prevention and giving workers and families ‘voice’.[3]

Financial support for the families now bereft of a primary ‘breadwinner’ was limited and entirely inadequate. The first Employer Liability Act had been introduced into the colony in 1886 (amended in 1893 and 1897), but only provided small prescribed amounts where workers or their families could demonstrate designated forms of negligence. It was the 1920s before no-fault workers’ compensation legislation was introduced, and it too only slowly improved in value. Notwithstanding increases in death-benefits over the past decade, it is still arguably inadequate for those families blighted by workplace death (especially the self-employed).[4]

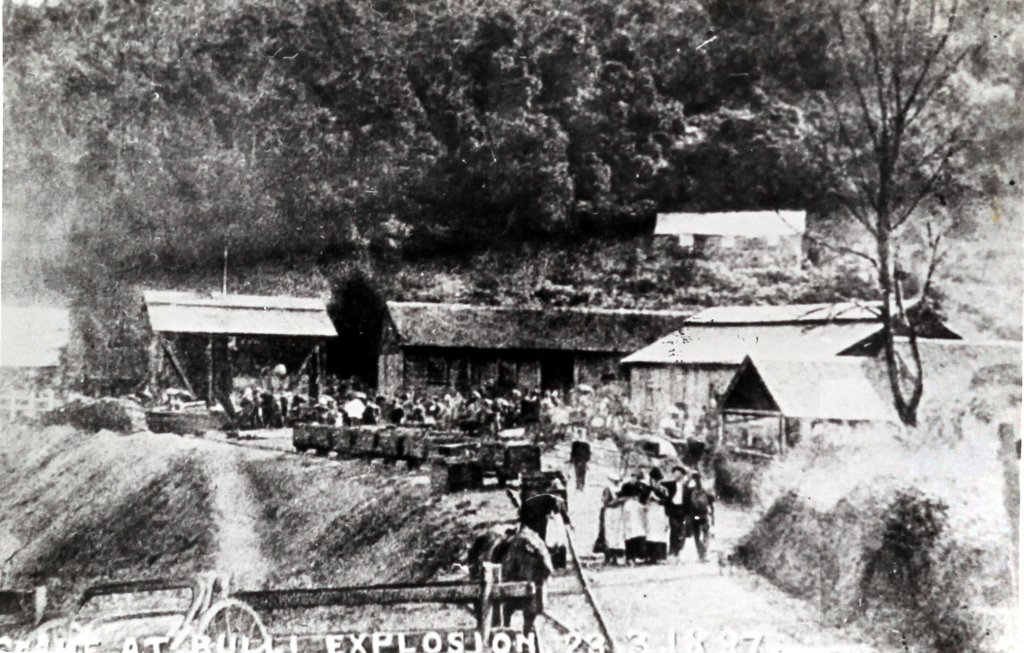

Scene at pit top following Bulli Mine Disaster of 1887

Source: University of Wollongong Archives, collection D158/3/55

The Hunter Valley coalminers union operated an accident fund, like many other mining unions, but if this existed at Bulli it would have been overwhelmed by the incident, even if payments were confined to members. Many Australian unions, especially craft unions and those in hazardous industries, operated accident and funeral funds but these were designed to address deaths to individual members, not the mass deaths occasioned by disasters. Richer unions also made ex-gratia payments to wives and children (including orphans) of members who did not meet the eligibility criteria, but this was discretionary and predicated on the union having sufficient funds (the CFMMEU mining division still makes direct payments to the families of members killed on the job). Following disasters such as mill explosions, ship losses and mine disasters, groups, individual unions and labour councils undertook community fund-raising appeals, for example following the loss of the Yarra Yarra in 1877.[5] While important, this voluntary approach left gaps and did not constitute a mandatory form of social-welfare.

Can we know anything of the impact of workplace death on families beyond these few observations? Can we know anything of the suffering, mental anguish and impacts of deaths on the Bulli miners’ families? Can more recent research help inform the past just as the past speaks to the present? It may come as a surprise to learn that in the 130 years since the Bulli disaster there has been very little research into the impact of workplace deaths on families – not just in Australia but globally. The exceptions are so rare as to be notable, including Sarah Gregson’s study of a fund set up for the families of the Titanic crew and several papers dealing with the impact on families of the Piper Alpha oil rig disaster in the North Sea in 1988.[6] This neglect has not arisen because workplace death is no longer a widespread issue. Fewer workers die in disasters like Bulli today – at least in countries like Australia with relatively effective safety laws and a strong and committed miners’ union.[7] But even in the 1880s most workers killed at work did not die in ‘disasters’ and many still die today at work, around 200 a year in Australia.

A decade ago, the NSW Construction Division of the then-CFMEU, which has been active on the part of bereaved families, funded a pilot study of the impact of workplace death. It entailed in-depth interviews with seven family members and identified an array of impacts and serious shortcomings in the institutional response to workplace death.[8] This led to an Australian Research Council Discovery Grant to explore the impact of workplace on families. This larger study reinforced findings about inadequate institutional responses, apart from those of some unions, and the critical role played by support groups like VOID (Voice of Industrial Death).[9] In addition to interviewing institutional representatives, the study included an international survey of family/bereaved affected by workplace death, and follow-up interviews with a number of those completing the survey to obtain more detailed insights into their experiences, needs and desires. Of the survey respondents 62% were Australian, 17% Canadian, 16% from the USA, and 5% from the UK. Around 90% of respondents were female, not surprising given that 90% of fatalities were male.

The following points can be made from the key findings. Amongst those surveyed, evidence indicated 61% experienced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 44% experienced major depressive disorders (MDD), and 42% experienced prolonged grief disorder (PGD). These and other findings did not vary in any significant way according to the country of the survey respondent.[10] These findings illustrate a significant degree of mental anguish following workplace death. Discussions of ‘closure’ are meaningless and misleading. Families do not overcome their grief and loss, although to varying degrees they learn to live with it. In other words, there is no closure. The study also identified significant effects on children, financial effects (especially self-employed), and the valuable role of self-help groups, like VOID, in providing information and support. These bodies urgently require support, especially to alleviate the enormous demands they place on key activists who can ‘burn out’. The NSW body (Workplace Tragedy Family Support Group) closed in 2019. Shortly after its demise, key activist Wendy Lark died, and this paper is written in no small part as a tribute to her life and memorable contribution to families and society more generally.

The survey and interviews identified several key things families wanted, namely:

- Clear and timely information of how/why the death occurred

- That the deceased was not dehumanised by legal processes

- Identification of responsibility and timely prosecution, if there was a breach of health and safety legislation, with significant penalties that will act as deterrent

- Remedial measures to prevent similar incidents in the future so other families are spared similar tragedy[11]

These expectations represent a rational and humane response to tragedy. While evidence we have on the families of victims in the past is sparse and fragmentary, this recent research provides some insights into the enormous toll exacted by workplace death then as now. At the time of the Bulli disaster there was mine safety legislation, but as an instrument of social protection it was clearly and manifestly inadequate. It took over a century of struggle for NSW (and Queensland) to secure more effective mine safety legislation, which is now regarded as world’s best practice. Even so, families of those killed in mines and other workplaces remain deeply disillusioned about the enforcement of OHS legislation, setting an important context for the push for industrial manslaughter provisions in these laws.[12] Their voice has seldom been heard in this debate – it deserves to be.

Michael Quinlan is emeritus professor of industrial relations at UNSW and has written extensively on worker health and safety, including the causes and impact of workplace fatalities, and labour history. His most recent book, Contesting Inequality and Worker Mobilisation in Australia 1851-1880, Routledge, New York will be published in August 2020.

Lynda Matthews is associate professor and Academic Lead of the Work and Health Research Team in the Faculty of Medicine and Health at the University of Sydney. Key areas of Lynda’s research include psychosocial consequences of fatal work injuries and related legal processes for next-of-kin and families; mental health rehabilitation and work; and psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery. Lynda has held advisory positions to the Federal Government in the areas of rehabilitation and mental health, and is currently an honorary associate professor (research) at Western Sydney Local Health District.

Philip Bohle is a professor at the University of Tasmania and has previously held professorial appointments at the Universities of New South Wales and Sydney. He is a member of the Research Foundation of the NSW Government Centre for Work Health and Safety and a Board member of the Working Time Society and the Scientific Committee on Shiftwork and Working Time of the International Commission on Occupational Health. He has published widely on workplace health and safety, with a particular focus on the effects of work organisation and psychosocial factors on health.

Endnotes

[1] D. Dingsdag, The Bulli Mine Disaster: Lessons from the Past (Sydney, NSW, Australia: St. Louis Press, 1993).

[2] ABC News, ‘Michael Welsh death: Workplace safety charge dropped over Mount Lyell copper mine fatality,’ Available at: www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-28/michael-welsh-mtlyell-death-cmt-safety-charge-dismissed/8848342 (accessed 25 January 2019).

[3] D. Walters and M. Quinlan, ‘Voice and resistance: Coal miners’ struggles to represent their health and safety interests in Australia and New Zealand 1871-1925,’ Economic and Labour Relations Review 30, no.4 (2019): 513-31.

[4] M. Quinlan, S.J. Fitzpatrick, L.R. Matthews, M. Ngo and P. Bohle, ‘Administering the cost of death: Organisational perspectives on workers’ compensation and common law claims following traumatic death at work in Australia,’ International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 38 (2015): 8-17; : L.R. Matthews, M Quinlan. G. Jessup and P. Bohle, Death at Work: Improving support for families. Financial Consequences for Families (Sydney, Australia: Work and Health Research Unit, University of Sydney, (2020).

[5] For an examination of these activities see M. Quinlan, Contesting Inequality and Worker Mobilisation: Australia 1851-1880 (New York: Routledge, in press).

[6] S. Gregson, ‘Women and children first? The administration of Titanic relief in Southampton, 1912-59,’ English Historical Review 127, no. 524 (2012): 83-109; D. Alexander, ‘Psychological intervention for victims and helpers after disasters,’ British Journal of General Practice 40 (1990): 345-348; D. Alexander, ‘Psychiatric intervention after the Piper Alpha disaster,’ Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 84 (1991): 8-11.

[7] M. Quinlan, Ten Pathways to Death and Disaster: Learning from fatal incidents in mines and other high hazard workplaces (Sydney: Federation Press, 2014).

[8] L. Matthews, P. Bohle, M. Quinlan and O. Rawlings-Way, ‘Traumatic work-related death in the construction industry: Experiences of victims’ families: A report prepared for the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union, Work and Health Research Team, Ageing, Work and Health Research Unit, (University of Sydney, 2011); L. Matthews, M. Quinlan, P. Bohle and O. Rawlings-Way, ‘The adequacy of institutional responses to death at work: Experiences of surviving families, International Journal of Disability Management 6, no. 1 (2012): 37-48; L. Matthews, P. Bohle, M. Quinlan and O. Rawlings-Way, ‘Traumatic death at work: consequences for surviving families,’ International Journal of Health Services 42, no. 4 (2012): 647-666.

[9] L. Matthews, S. Fitzpatrick, P. Bohle and M. Quinlan, ‘Investigation and prosecution following workplace fatalities: Responding to the needs of families,’ Economic and Labour Relations Review 25, no. 2 (2014): 253-270; M. Quinlan, S.J. Fitzpatrick, L.R. Matthews, M. Ngo and P. Bohle, ‘Administering the cost of death: Organisational perspectives on workers’ compensation and common law claims following traumatic death at work in Australia,’ International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 38 (2015): 8-17; M. Quinlan, L. Matthews, P. Bohle and S. Fitzpatrick, ‘Employer and union responses to traumatic death at work: Evidence from Australia,’ New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations 40, no. 3 (2015): 1-23; L. Matthews, M. Quinlan, S. Fitzpatrick, P. Bohle and M. Ngo, ‘Bereaved families and the Coronial response to traumatic workplace fatalities: Organizational perspectives,’ Death Studies 40, no. 3 (2016): 191-200.

[10] L. Matthews, M. Quinlan and P. Bohle, ‘Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression and prolonged grief in families bereaved by sudden, fatal work injuries,’ Frontiers of Psychiatry (2019) https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00609/full

[11] M. Ngo, L. Matthews, M. Quinlan and P. Bohle, ‘Bereaved family members’ views and experiences of the value of Coronial Inquests into fatal work incidents,’ OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying (2018) https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222818819344; M. Ngo, L. Matthews, M. Quinlan and P. Bohle, ‘Information needs of bereaved families following fatal work incidents,’ Death Studies 44, no. 8 (2019): 478-489. DOI: 10.1080/07481187.2019.1586792.

[12] L. Matthews, M. Quinlan, O. Rawlings-Way and P. Bohle, ‘Work fatalities, bereaved families and the enforcement of OHS Legislation,’ Journal of Industrial Relations 61, no. 5 (2019): 637-656.