The Life and Death of Percival Stanley ‘Jack’ Brookfield[1]

Paul Robert Adams

Percival ‘Jack’ Brookfield died on 22 March 1921. He succumbed to wounds sustained attempting to stop a deranged Russian gunman, Koorman Tomayoff, who was shooting at passengers at the Riverton railway station in South Australia. Tomayoff fired 40 times and shot four people before Brookfield intervened and was fatally wounded, dying later that day in Adelaide Hospital.[2] When asked why he had confronted the gunman, Brookfield said, “I did it for the women.”[3]

Many of the eulogies pointed out how consistent Brookfield’s death was with the way that he lived his life. Mary Gilmore wrote:

For just as he lived his days, each one,

So in the end he died.[4]

Donald Grant put the sentiment like this: “and the manner of his death was in complete harmony with the manner of his life”.[5]

A rider with a red flag leading Brookfield’s funeral procession

Source: Broken Hill Outback Archives

A train festooned with wreaths carried Brookfield’s body up to Broken Hill and his funeral, held three days later, was the greatest funeral ever held in

Percy Brookfield in 1915

Photograph by C.H. Conlon, Broken Hill

Source: State Library of Victoria

Broken Hill. A rider on a black horse carrying a red flag led the march, followed by members of parliament, union officials and labour representatives. Almost every organisation in Broken Hill was represented in the official procession which included thousands of unionists and members of women’s groups. After them came 127 vehicles. Most of the town’s 24,000 inhabitants attended. Six black horses festooned with red ribbons pulled the hearse and the Workers’ Industrial Union Band played ‘The Dead March’. At the graveside, the band played and a chorus of thousands sang ‘The Red Flag’ and then ‘Should I Ever Be a Soldier’.

There were no public prayers, instead Brookfield’s friend and colleague, Jack O’Reilly said:

I am today honoured with the sad task of saying these last words of him whom I believe to be the grandest man that ever lived … the greatest champion that the people have ever had … the dearest, closest friend I have ever had … His heart was the best that ever beat in a human breast. There was not a weak link in the great chain of manly principles … there was not a weak spot in his character.

As he finished speaking, O’Reilly wept uncontrollably, as did many in the crowd.[6]

The sentiment was sincere and the spectacle was grand, and yet less than six years before this display Brookfield was an anonymous, quiet, almost teetotal, miner. Then, as his friend Ernest Wetherell(subsequently a prominent NSW Parliamentarian) said, Brookfield “rose like a meteor in public life”.[7]

Liverpool, Windjammers, Prospecting and Mining

Brookfield was born in Wavertree, Lancashire, England in 1875.He grew up in the nearby Liverpool suburb of Toxteth Park and went to sea as a boy of about 13. He sailed for the last time as a mariner in 1894, disembarking the Godiva in Melbourne on 27 November 1894. His discharge certificate was marked ‘Very Good’ for both ‘Character for Conduct’ and ‘Character for Ability’.[8]

Brookfield carried a swag and went prospecting. Years later he was to say that there was hardly a field where more than a pennyweight of gold had been found in which he hadn’t spent some time.[9]Brookfield travelled to Broken Hill in 1910, went back to Cobar in 1912, and returned to the Hill in 1914. He then went prospecting one last time before again returning to Broken Hill, taking work as a miner and timberer on the South Mine, then the BHP mine where he had worked previously.[10]

The Strike for the 44-Hour Week

Brookfield had not long returned to work at the BHP mine when an industrial dispute erupted. In September 1915, a mass meeting of the Amalgamated Miners’ Association (AMA)voted to cease working Saturday afternoons. The following week, at a well-attended AMA meeting, a small majority voted for a return to work. The underground workers, however, met separately and voted not to work the shift. Eight Hours’ Day was the following Thursday. Thousands of unionists marched wearing cards saying, “If you want a 44-hour week TAKE it.”[11]

A strike committee was formed with George Kerr as chairman and John Joseph ‘Jack’ O’Reilly as secretary. For three months the ‘undergrounders’ became a de facto separate branch of the AMA.[12]Brookfield was one of the first elected to the strike committee and it was here that he first came to notice amongst the miners. He rose to prominence, Ern Wetherell recalled, as “one of the minority”, one of the militants.[13]

Industrial accidents and diseases were problems in Broken Hill from the beginning. An average of 20 men were being killed each year, and many more were seriously injured. Pulmonary diseases were obviously and unacceptably common. A disproportionate number of miners were dying of pneumonia, and increasing numbers were getting ‘miner’s lung’ (miners’ phthisis or pneumoconiosis).[14]

Many men believed that time out of the mines was therapeutic. The undergrounders were working a six-day, 48-hour week, and they wanted to have more time above ground. They especially wanted to have Saturday afternoons off to relax and play sport (the sport of choice being Victorian Rules Football) or engage in other recreations such as horse-racing or drinking in Broken Hill’s many pubs.[15]

The undergrounders continued to refuse to work the Saturday afternoon shift and– whether it was the perceived support of the Arbitration Court, an attempt to divide the workers, or sheer loss of patience – at the beginning of 1916 the companies moved to lay off those who did not work the shift. This led to the whole AMA joining the strike, and reunification of the union.[16]

The very radical Mick Considine was at the time AMA President; Ian Turner observed that the virtual secession of the undergrounders “was a revolt of rank-and-file militancy against the most militant union leadership then existing in Australia”.[17] The AMA may not have had the most militant leadership in Australia but it had a reputation for militancy that was built on major confrontations over the previous decades, primarily the 1892 strike and the Great 1909 Lockout.

The 1892 Strike

In 1892, tensions between the workers and the mining companies intensified as the year progressed.[18] Two AMA delegates were sacked while out of town on union business.[19] Then the companies declared their intention to unilaterally break with the existing agreement. The employees withdrew their labour four days later.[20]

The strike that followed was a bitter 18-week battle. At the mine owners’ request, the NSW Premier, Sir Henry Parkes, sent hundreds of police to the town to protect the ‘free labourers’, or ‘blacklegs’, that the companies brought in to break the strike. There were frequent altercations.[21]

In one famous action, large groups of the town’s women launched sortie after sortie, running in among the strike breakers and attacking them with domestic implements. The police were reluctant to use the same violence that they applied to the men.[22]

The strike ended when seven of the strike leaders were arrested, five by police armed with rifles and fixed bayonets, and stood before a ‘cocky’ jury in Deniliquin. Acting Justice Backhouse handed out sentences of between three months and two years.[23]

The Great 1909 Lockout

The other most notable industrial action was the Great 1909 Lockout. Once again hundreds of armed police were sent to protect the mines and ‘free labourers’.[24]

The dispute is famous for images of the so-called ‘Scabs’ graves’; Tom Mann speaking outside the Trades Hall; the trains to hear Tom Mann speak from over the South Australian border; the organised marches; and the military-like changing of the pickets. These images appeared to represent the epitome of militant unionism. Erik Eklund and I have argued that these photographs contributed to the reputation of militancy that attracted to Broken Hill many of the radicals who played key roles over the following decade, a period Wetherell called the “Stormy Years”.[25]

Whether Brookfield was drawn to Broken Hill by its radical reputation is not known, but Wetherell certainly was. He wrote:

I wanted to see this Mecca, Broken Hill, to be part, if I could, of man’s surge forward to better times and to be in the Labor Movement that seemed to my teenage mind to be moving rapidly towards this goal.[26]

The reality is that the Great 1909 Lockout did not result in a victory for the unionists; it was a hard-fought draw. The Strike for the 44-hour Week, however, was a victory for the undergrounders. It was a hugely significant industrial action because this was wartime, Broken Hill’s production was an important part of the national economy, and the mines’ products were needed for the production of weapons.[27]

The Commonwealth Government became involved, but the situation was intractable. The undergrounders refused to work the Saturday afternoon and the companies refused to give them the 44-hour week that they sought. The mines stood idle.[28]

Jack O’Reilly cut the Gordian Knot when he suggested that, as a temporary measure, work be resumed four days per week. Furthermore, the proposal was presented as coming from Government. This was a face-saving strategy so neither side had to relent. Work was resumed, then the Arbitration Court came down in favour of the undergrounders who were granted the 44-hour, five-and-a-half-day week.[29]

The strike was extremely unpopular and the disruption to the factory operation was a major focus of those opposing the strike. The miners were accused of helping Germany and sacrificing ‘our boys’. Some people believed that the closing of the works caused the failure of the Gallipoli campaign.[30]

The events that followed in Broken Hill inflated that treacherous image.

Labor’s Volunteer Army

The Strike for the 44-hour Week transformed Brookfield and he grew in confidence. While at first, he would only have been addressing his peers, miners and other underground workers, his confidence and abilities grew as he became used to addressing the Committee and then the mass meetings. In all these actions his status rose as, according to Wetherell, “his militant spirit was tempered with judgment”.[31]

Brookfield spoke at meetings of the whole AMA, and its executive, and then he was sent to Melbourne as a witness in the case the union presented to the Arbitration Court. There he met many prominent unionists and political radicals. During this time his profile was raised in Broken Hill where he had become a leading member of the AMA. [32]Soon, Brookfield was addressing organisations that had sprung from the AMA and, within a couple of years, he addressed huge crowds in Sydney’s Domain.[33]

Brookfield’s emergence from the Strike for the 44-hour Week as a respected union member made possible his next role, as president of an anti-war organisation. The numbers of new recruits to the war fell and this led to increasing demands for conscription.[34] In response, Broken Hill’s mass anti-conscription organisation was formed at the end of July 1916. Brookfield was elected president and, in keeping with the military tone of Labor’s Voluntary Army for Home Defence (LVA), he was subsequently often referred to as ‘General Brookfield’.[35] If his position in the Strike for the 44-hour Week had given Brookfield the confidence to speak publicly, the role at the helm of the LVA “brought him out of his shell with a vengeance”.[36]

Brookfield saw the war as a contest between imperial powers, whereas he was interested in the wellbeing of working men and women. After the Strike for the 44-hour Week, the unionists feared industrial conscription – that they might be forced to work in the mines.

Brookfield was not a pacifist and, as its name suggests, the LVA was not a pacifist organisation. Its role was one of resistance. Its members were ‘eligibles’ who publicly refused to enlist or to be conscripted.[37] The LVA, which included a ‘Ladies Corps’, was inspired by the Women’s Peace Army, whose motto was, ‘We War Against War’.

The LVA collated and printed its own collection of songs in Labor’s Volunteer Army Song Book.[38] LVA Volunteers marched around town singing anti-war songs, like Joe Hill’s ‘Should I Ever Be a Soldier’, which was Brookfield’s favourite.

This spectacle was immensely irritating for some and a large group of bruisers were bought into town to teach the LVA a lesson. They set upon an LVA meeting wielding a variety of weapons, including golf clubs. A wild brawl followed as LVA members attempted to defend themselves. Brookfield flattened several attackers before the crowd knocked him to the pavement and kicked him while he was down. One assailant stabbed him in the mouth with an umbrella while he was on the ground.[39]

Brookfield was helped to a chemist to have the wound treated before he managed to race down Argent Street and defend the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) Hall from the attackers. Constable John Burke testified that Brookfield had hit seven or eight of the attackers. According to Wetherell, the police looked on “non-plussed[sic]” as Brookfield kept the crowd at bay. When the action was over, the police calmly turned and arrested Brookfield.[40]

The LVA President and Secretary, Brookfield and Ted Sinclair, were convicted of riotous behaviour. None of the attackers were charged.[41]

The Sturt MLA

In December 1916, under pressure from the Broken Hill Labor Party branch over his stance on conscription, the Member for Sturt, John Henry Cann, secured a position as a Railway Commissioner and resigned from parliament. Cann had been in parliament since before the 1892 strike and had held all the top jobs the Legislative Assembly had to offer, except Premier. But his time had come and he resigned from parliament, forcing a by-election.[42]

During this period, ‘General’ Brookfield was repeatedly prosecuted and fined under the War Precautions Act. Ultimately, his fines totalled more than £700.He was in gaol when his colleagues encouraged him to stand for the vacant seat. A first, he dismissed the suggestion but later became very keen to do so.

Brookfield was out of gaol for less than two weeks when he launched his campaign in Broken Hill’s Central Reserve.[43] A furious round of campaigning followed and ended, following LVA tradition, with a torchlit procession and rally at the corner of Argent and Chloride Streets.[44] The result was a victory for Brookfield by 562 votes (3301 to 2739). Brookfield the man won the day, but the triumph was felt by all the militant unionists in the town, especially the AMA leadership. Brookfield’s jubilant supporters carried him down Argent St on their shoulders.[45]

Parliament was prorogued at this time and the general election was called before Brookfield could even take his seat. Brookfield made a speech in which he said that he would only fight under the red flag and not the Union Jack. The sensation reverberated around the country. ‘Red Flag Brookfield’ was a bogeyman during this campaign. Even the London Times reported that “all Australia is indignant”.[46] Brookfield was accused of disloyalty, parasitism and cowardice, of being anti-British and pro-German.[47]

The Labor opposition leader, John Storey, blamed Brookfield for losing the party six seats.[48] However, Brookfield’s popularity grew in Broken Hill and his majority in Sturt increased.[49]

There were moves to have Brookfield barred from the NSW Parliament even before he arrived in Sydney. The NSW Political Labour League (PLL) tried to expel him but could not quite rise to the challenge. Brookfield refused to resign, and forced the hand of the PLL, saying, “that if anything he had done justified it, they should be men enough to expel him straight out”.[50]

Once in Parliament, Brookfield carried on with his direct, singular path, openly championing the causes and colleagues that he believed in. He continued with his relentless attack on the war. Those who had hoped that his election would temper his statements were disappointed. Brookfield said, “I don’t care a damn who wins the war, whether it is England or Germany, what I want is the war to stop, I want peace.”[51]

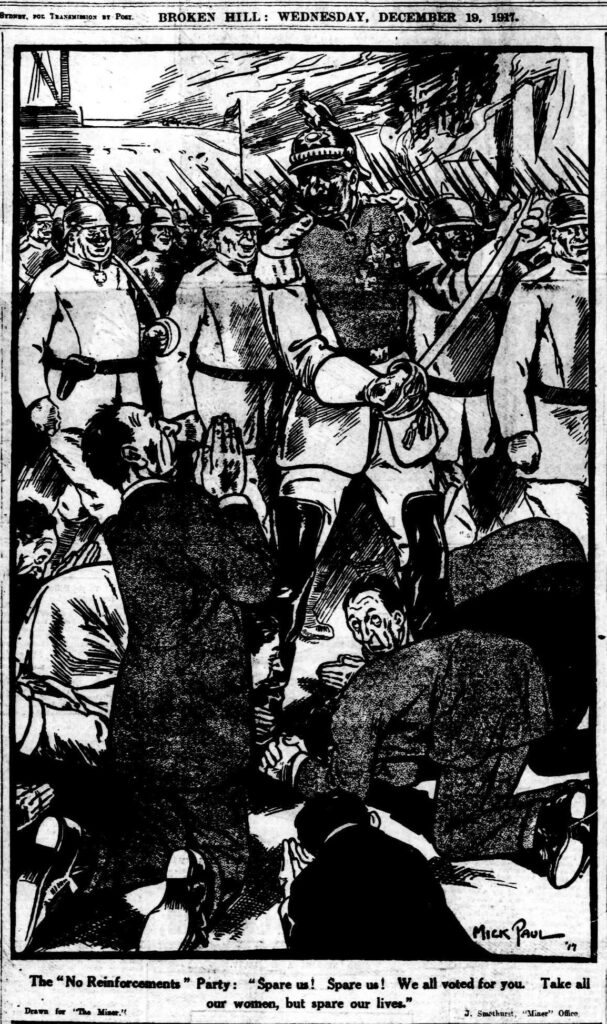

Cartoon depicting Brookfield and Considine as kowtowing to Germans

Source: Broken Hill Outback Archives

Likewise, he continued his crusade against conscription throughout the second referendum in 1917. Now a national figure, Brookfield drew a huge crowd to his address in the Domain on the matter.[52] Brookfield and fellow Broken Hill unionist Mick Considine were included in the list of the six most despised men in the country in a famous conscriptionist pamphlet called The Anti’s Creed.[53]

As opponents of the war and conscription, Brookfield and his colleagues were despised, labelled traitors and cowards and said to have cold feet. One of the most well-known anti-war campaigners was the IWW man, Donald Grant, and it was he who said that Brookfield was the “best hated man in Australia”, meaning that, of all the hated men in Australia, that is, of all of the opponents of conscription, Brookfield was the best.[54]

The Sydney Twelve

Brookfield used his position in the NSW Parliament to fight for other unpopular, all-but-lost causes of the political Left, including the case of the ‘Sydney Twelve’ who had been jailed for sedition. Following a series of fires in Sydney, these 12 members of the IWW had been imprisoned for terms ranging from five to 15 years.[55]

While some of them may have been guilty of some of the charges, the convictions were unsound. One instance that most incensed Brookfield was the allegation of a conspiratorial meeting in Sussex Street when a plot was supposedly being concocted, which could not have occurred as the police alleged, as prison records proved the accused was in Long Bay at that period. Still, Justice Pring dismissed the alibi and insinuated guilt despite the evidence, saying, “If you were not there on that day, you were there on another day.”[56]

A Defence and Release Committee was established at the behest of Henry Boote, editor of The Australian Worker, and Ernie Judd of the Socialist Labor Party, both of whom played central roles in it. Brookfield had been elected on the promise that he would “fight like hell” for the IWW Twelve.[57]

Judd gathered allegations of police impropriety, including the fabrication of evidence from a former IWW member, Henry Christopher ‘Harry’ Scully, who was a paid police witness.[58] Brookfield seized a moment when the government did not have the numbers in the House to release the information in Parliament and to repeat his demands for a royal commission.[59]

This led to a Commission of Inquiry being conducted by Justice Philip Street. Justice Street was not inclined to doubt the Crown witnesses, especially the police, but when it was unavoidable, he gave them the benefit of the doubt. He found that there were no “fresh facts … raising any doubt in my mind as to the guilt of the convicted men”.[60]

Although Street was not convinced, not everyone was so comfortable to have the men remain in gaol.

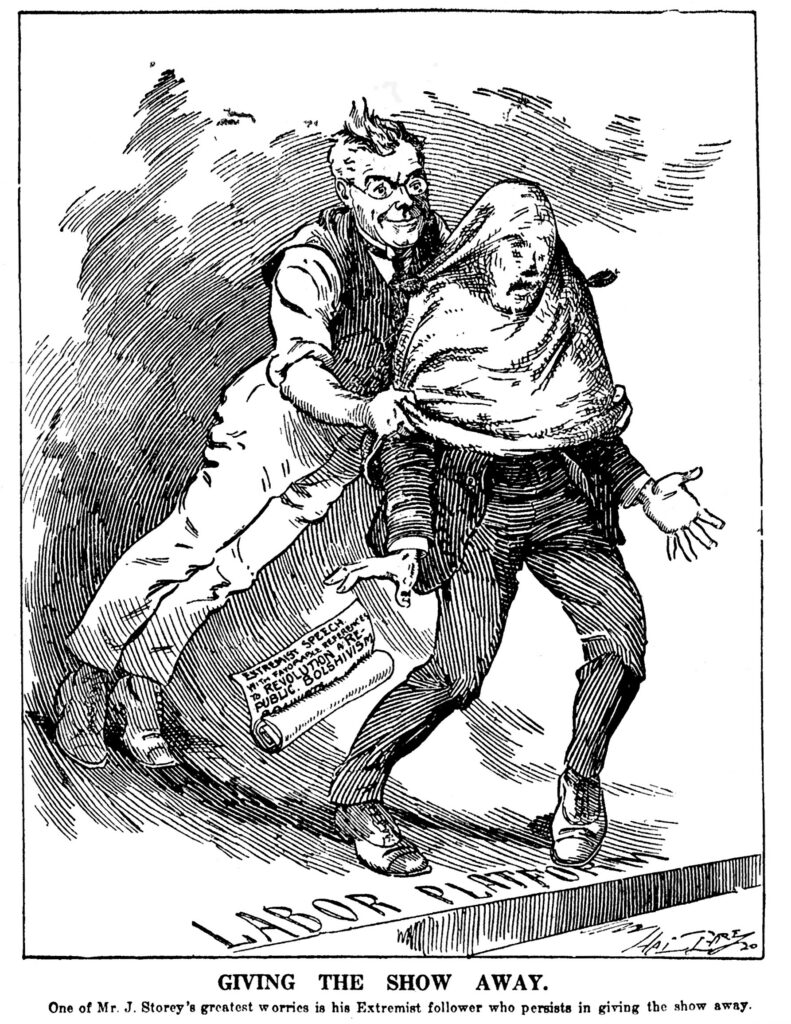

Cartoon depicting Premier Storey and Brookfield (in bag)

Source: Broken Hill Outback Archives

1920 NSW Election

In 1920 another state election was held. This was during the time of NSW’s brief experiment with multi-seat electorates and the reformed Sturt was a three-seat electorate.

Brookfield had been expelled from the ALP, and the issue had split the Barrier District Assembly of the ALP (BDAALP) into two factions named for the places where they held their meetings: a Druids’ Hall faction supportive of the ALP state executive, and a Trades Hall faction supportive of Brookfield. The Sturt electorate was contested by three Nationalists, three representatives of the BDAALP (Druids’ Hall), and three BDAALP (Trades Hall) candidates (Brookfield and O’Reilly being joined by the former Broken Hill Labor Mayor, Thomas Francis Hynes). Brookfield was re-elected on his 4,357 first preferences (27.53 per cent), the highest vote of any candidate. The other two successful candidates were Mark Davidson (BDAALP Druids’ Hall) and Brian Doe (Nationalist).[61]

The State election resulted in a hung parliament. After gaining agreement that a suitable inquiry into the gaoling of the Sydney Twelve would be held, Brookfield did not re-join caucus, but rather joined Paddy Minahan, who had been returned as an Independent Labor member for Sydney, in supporting the formation of a Labor government under John Storey.[62]

After the Labor Government was elected, Justice Norman Kirkwood Ewing conducted an inquiry that led to the release of the 12 IWW men.[63]

Despite this support, Brookfield and the industrialists of the Barrier labour movement decided that they were not compatible with the ALP State executive. On 12 April 1920 the BDAALP (Trades Hall) declared itself independent of the governing party and adopted the name of the Industrial Labor Party (ILP).[64]

Paul Freeman

Another unpopular cause in which Brookfield played a prominent part was the fight against the deportation of anti-war activist Paul Freeman, who had been captured by the authorities in Queensland, whisked down to Sydney and placed on a steamer bound for San Francisco. He would have disappeared from the country without anyone being the wiser, except that the ship broke down and returned to port. After being bundled in and out of solitary confinement at the Darlinghurst lockup, Freeman was put back aboard the Sonoma in time for it to sail again on 29 January, 1919. When the ship arrived in San Francisco Freeman refused to confirm his nationality, so US immigration denied the deportee entry and he was returned to Sydney.[65]

Freeman was of disputed nationality. The authorities claimed he was German, or had German parents, and were deporting him as an enemy alien. Freeman was likely born in the United States of German parents.[66]

Freeman had worked as a miner in Broken Hill where he had been a radical unionist and an LVA member, so he was known to Brookfield. Strangely, however, the two had met and been friendly decades before in the Chilean port of Iquique, when their ships were docked there.[67]

After Freeman was returned from San Francisco, he was held on board the Sonoma incommunicado, but managed get a message to union friends in Sydney. Two members of the NSW Legislative Assembly with union connections, Thomas Mutch and James Dooley, bought tickets for the return voyage to the United States to ensure that Freeman was properly treated.[68] While the Sonoma was berthed in San Francisco, Freeman was held in the Angel Island Immigration Station, and then placed back on board for the return voyage.[69]

Denied his liberty, and now having crossed the Pacific four times, Freeman went on a hunger strike and the issue exploded in the press. A delegation, including Brookfield, was allowed onboard. Protests took place on the docks where large groups of police were gathered and then, to huge applause, Freeman was carried off the ship.[70]

Some of the protests degenerated into violent confrontations. In one of these, about 5,000 people marched down to Circular Quay where the Sonoma was berthed, and were set upon by the police.[71] Brookfield was still recovering from the Spanish Flu but managed to save several people from the indiscriminate violence before being struck on the chest above the heart. As Brookfield put it, when the crowd reached the dock “the Police charged it and split open the heads of men and women for simply protesting. Those that had called me cold-feeted and other things the previous day ran away and left me to get a good bateening [sic].”[72] Months later Brookfield had an operation in Adelaide but he never fully recovered from that blow.[73]

Ultimately, these battles were futile. Freeman was deported to Germany in October 1919.Strangely, he came back Australia as a Soviet secret agent, Comrade Miller, in late 1920 before returning to Moscow in 1921.[74]

Peter Simonoff

Another interesting Soviet figure who received Brookfield’s support was Peter Simonoff. Simonoff had been an underground trucker when he and Brookfield worked in the same mine, and he joined the IWW Local in Broken Hill.[75]

After the revolution, the Soviets appointed Simonoff as the Consul General in Australia, but the Commonwealth refused to recognise him. The lack of official recognition did not dent Simonoff’s enthusiasm for his new role. He moved to Melbourne and set up his Bolshevik ‘Consulate’. The Left welcomed Simonoff’s appointment. Two of his biggest supporters were Mick Considine, then Member for the federal electorate of Barrier, and Brookfield.[76] The trio were called the ‘Broken Hill Three’.[77]

Simonoff was tried and convicted under the War Precautions Act. Without Brookfield’s intervention he “would have been imprisoned without trial”.[78] Simonoff was fined £50 on each charge with the option of six months gaol, and remanded until sureties of £400 were paid.[79]

When he discovered the Consul General’s predicament, Brookfield provided bail and took him into his own home at 22 Sir John Young Crescent, Lower Domain (now Woolloomooloo).[80] Simonoff appealed but this was dismissed by Judge Backhouse. Simonoff then refused to pay the fines as that would legitimate his non-recognition as the Soviet Consul General, so he was sent to Long Bay Gaol.[81]

Brookfield threw himself into a public defence of Simonoff. When Simonoff was released after serving four months he returned to Brookfield’s bedsit. It was from there that he played a pivotal role in the creation of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) and the associated clandestine entity, the ‘Secret Seven’.[82]

Incidentally, Freeman, the Soviet agent calling himself ‘Mr Miller’ was operating independently from, and against the wishes of Simonoff, who was apoplectic that he had not been informed and that the clandestine operative was promoting a rival faction of the CPA.[83]

Despite their shared accommodation, Brookfield was to some extent unaware of Simonoff’s activities and innocently forwarded money that had been secretly supplied to the Soviet Consul General to the strikers in Broken Hill.[84]

Simonoff was full of praise for Brookfield, whom he regarded as an exceptional human being completely devoted to the cause. “I don’t think Jack [Brookfield] had any sense of fear, just as he could not understand how he could be dishonest in anything at all”, he explained. “These two things were absolutely impossible for him. “Once he was politically active, Simonoff wrote, Brookfield “had no personal life at all, everything was for the working class, absolutely and unconditionally”.[85]

The Big Strike

Through this period Brookfield was a driven man and one of the things driving him was the Big Strike in Broken Hill. The Big Strike, which erupted in May 1919 and lasted until November 1920, is one of the greatest industrial battles in Australian history.

The union’s log of claims included:

A five-day week of six hours per day;

£1 per shift minimum wage;

Qualified ambulance men;

Regular analysis of the air underground; and

Compensation for those afflicted by occupational diseases.[86]

One significant moment in the development of the CFMEU was when the Broken Hill miners’ union, the AMA, joined with the Australasian Coal and Shale Employees Federation (ACSEF) in 1917.[87] The AMA maintained its identity by calling itself the Amalgamated Metalliferous Affiliation of the ACSEF. The amalgamation was seen as part of the formation of the mining division of the One Big Union, and the AMA subsequently changed its name to the Workers’ Industrial Union of Australia.[88]

The AMA was already a powerful union but the amalgamation produced something that had probably never been seen in this country; it combined the large, desperate, radical, ‘informed’ and strike-hardened union in Broken Hill with the larger union resources on the east coast. The former AMA was the tip of the spear that was going to break through for the whole union, and that is what happened.

Brookfield was in Sydney as a Member for Sturt, holding the balance of power as the sole Industrial Labor Party member, and Jack O’Reilly was the AMA representative there. Both were wielding their influence and raising money for the strikers.

The result hinged on a Board of Trade inquiry into mining diseases in Broken Hill which was presided over by Justice Walter Edmunds. Brookfield kept the union in Broken Hill informed, sending messages couched in horse racing terms. “Colt going well for seven furlongs race”, said one telegram. Suddenly, however, the judge’s tone changed. Stunned, Brookfield and O’Reilly perceived that the case was now lost. Brookfield wired: “Colt broken down. No chance in seven furlongs race. Amazed. Letter following.”[89]

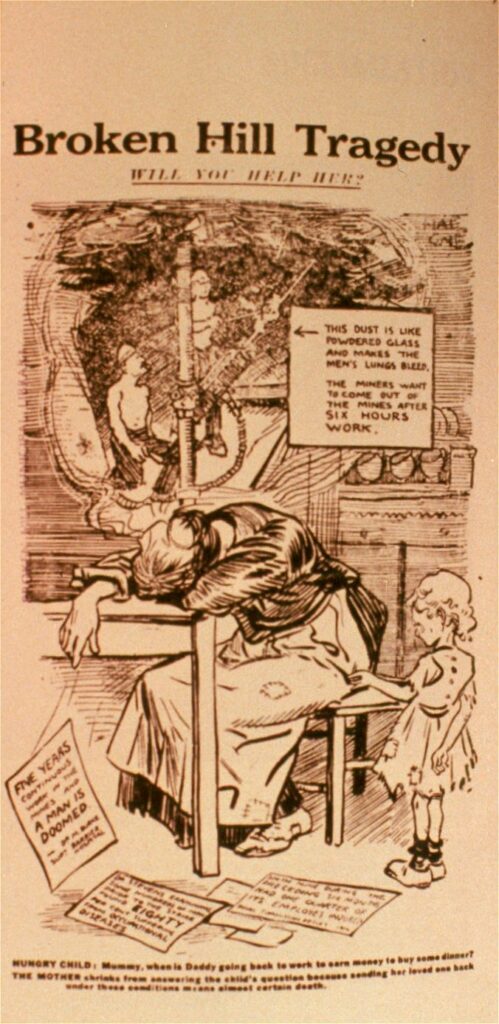

Broken Hill Tragedy an image from the Big Strike 1919-1920

Source: Broken Hill Outback Archives

What had turned Edmunds remains a mystery. Still, he released a report rejecting the union’s case. The strikers were on their last legs, having been on strike for 16 months but, once again, “the ever fertile brain of J.J. O’Reilly” found a key. O’Reilly knew that Justice Edmunds coveted the upcoming role of Royal Commissioner to examine the railway workers’ strike of 1917. O’Reilly argued that His Honour would understand that the changes that would make the Broken Hill mining industry safe had yet to be implemented and some ‘temporary’ accommodation would be necessary, that there was the prospect of a statewide-strike, and the sought-after Royal Commissioner position could be his if a more definitive decision could be made.[90]

Brookfield’s hold on the balance of power gave him the necessary leverage to put O’Reilly’s plan into action. He persuaded the Premier, who persuaded Edmunds. In September 1920, Justice Edmunds presented his final decision. The 35-hour week of five shifts, seven hours a day, was granted to the underground workers. A new award was negotiated and the strike declared over. The Workmen’s Compensation (Broken Hill) Act 1920, the development of which included very significant contributions by Brookfield, followed.[91]

One month later it became obvious that the Barrier miners were the shock troops for the whole industry as the ACSEF served a similar log of claims.[92]

The Assassination?

The mine owners resented the outcome of the strike and were slow to recommence full operations. The NSW Government appointed a Select Committee to investigate the metalliferous industry’s decline, and it, including Brookfield, held hearings in Broken Hill.[93]

Returning to Sydney via Adelaide and Melbourne, Brookfield was in the refreshment room for the breakfast stop at Riverton railway station in South Australia when the shooting began. Tomayoff fired 40 shots and wounded four people before Brookfield intervened and was shot. He died in Adelaide Hospital later that day.

Brookfield was an extreme radical who was associated with saboteurs, the IWW, Russians and communists, he held the balance of power in NSW, and he was shot, so the circumstances lend themselves to suspicion, and his death has been called an assassination many times. Instances are as diverse as Geoffrey Blainey’s great history of the Barrier mining industry and Wetherell’s unpublished manuscript, ‘The Stormy Years’.[94] The suggestion is even in Frank Hardy’s Power Without Glory, regarding ‘Percy Blackwood, Labor member for Broken Hill’.[95]

The military authorities regarded Brookfield as being in league with Simonoff. Military Intelligence recognised ‘Comrade Filbrom’ in Simonoff’s correspondence as an alias for Brookfield.[96] The authorities had surveilled Brookfield from the time of his speeches in the Central Reserve in Broken Hill as ‘General Brookfield’.[97] It was obvious that Military Intelligence was intercepting Brookfield’s mail, as it got to the point where it interfered with his affairs.[98]

Despite his closeness to Simonoff, Brookfield did not join the Communist Party or the ‘Secret Seven’.[99] The Sturt MLA seems to have played his politics straight and in public.

The suggestion that Brookfield’s death was an assassination likely stems from the mysterious and untested utterances of the man who shot him. As he was being remanded in Adelaide Gaol, Tomayoff said, “You no forget to tell Judge I get one hundred pounds to shoot Brookfield.”[100]One month later, Tomayoff was brought before the court charged with murder. The defendant muttered “I do not understand” and three medical professionals declared him to be of unsound mind, so he was committed to Parkside Mental Hospital ‘at the governor’s pleasure’.[101] Tomayoff was an inmate there until his death 27 years later.[102] It is easy to agree with Kennedy’s observation that “the inquiring historian cannot help but regret the crown’s refusal to prosecute”.[103]

Tomayoff had every reason to be unhappy. His woman friend had died days before he left Broken Hill, he had quarrelled with his housemates, and he was jobless.[104] It may be that he was depressed and his statement is mischievous. Furthermore, his statements are curious and inconsistent. Tomayoff also said “I sorry I shoot Mr. Brookfield, no sorry I shoot the others.”[105] The witness accounts at the Coroner’s Inquiry suggest that Tomayoff turned his attention, and his gun, on people, including Brookfield, as they appeared, and this would be consistent with the conclusion that the Russian was despondent and angry.[106]

The Sturt Vacancy

NSW’s brief experiment with multi-seat electorates complicated Brookfield’s replacement in the Legislative Assembly. It was expected that Thomas Hynes, who received the second highest number of votes among the Trades Hall candidates, would be installed as the Member for Sturt, but Premier Storey obtained legal opinion that, as Brookfield voted with the government, the next ALP candidate should be installed.[107]

So, as it were, Brookfield was gone without even leaving a shadow in the House.

Brookfield’s memorial in Broken Hill cemetery

Photograph courtesy of Paul Adams

Paul Robert Adams was born in Broken Hill and holds a PhD from the University of Sydney. He worked for NSW parliamentary committees and lectured in media and communications at the University of New England before holding senior positions in private higher education.

Endnotes

[1] Much of the following is taken from Paul Robert Adams, The Best Hated Man in Australia: The Life and Death of Percy Brookfield 1875-1921, Puncher & Wattmann, Glebe, 2010.

[2] The Advertiser (Adelaide), Wednesday, 23 March 1921, 9.

[3] Observer (Adelaide), Saturday, 26 March 1921, 13

[4] Mary Gilmore, ‘How Brookfield Died’, dated 23 March 1921, in The Australian Worker, March 31, 1921.

[5] Barrier Daily Truth (BDT), 1 April 1921.

[6] BDT, 26 March 1921, and Sydney Sun, 26 March 1921.

[7] Ernest Wetherell, ‘Industrial History of the “Stormy” Years of 1910-1921’, unpublished typescript, Outback Archives, Broken Hill City Library (OA), 331.88/wet.

[8] Brisbane Courier, 7 November 1894, and Certificate of Discharge, Port of Melbourne, Victoria. A copy of Brookfield’s Certificate of Discharge was provided by Robert Brookfield.

[9] Gilbert Giles Roper, Labor’s Titan: The Story of Percy Brookfield, 1878-1921, eds. W. Scarfe & A. Scarfe, Warrnambool Institute Press, Warrnambool, 1983, 14.

[10] ‘Broken Hill Gaol Entry Book’, New South Wales State Records Office (SRO), 5/1441, ‘Percival or John Brookfield’, ‘Police report by Inspector Miller to Inspector General of Police in Sydney (copy to Military Intelligence in Adelaide), 1/2/17’, in ‘IWW Papers’, SRO, 7/5590, Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 2, 4, Simonoff, ‘Brookfield’, BDT, 16 January 1917, and AMA Members’ Ledgers, 1914-1916, OA, 95/4/2/30-34.

[11] George Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill, Melbourne, Fraser and Jenkinson, 1918; facsimile ed., Libraries Board of SA, Adelaide, 1965, 185.

[12] Ibid, 184-185.

[13] Ibid, 194, and Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 2, 5, 11-12.

[14] Brian Kennedy, Silver, Sin, and Sixpenny Ale: A Social History of Broken Hill 1883-1921, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1978,16-17, 62-63, 78-79.

[15] Ibid., 16.

[16] BDT, 17 December 1915, and 11-12 January 1916.

[17] Ian Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics: The Dynamics of the Labour Movement in Eastern Australia, 1900-1921, revised edition, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1979, 6.

[18] Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale,64-6.

[19] Barrier Miner (BM), 9, 14 March 1892.

[20] Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill. 21-23.

[21] Ibid.,49.

[22] Sandra Bloodworth, ‘Militant Spirits: The rebel women of Broken Hill’, Rebel Women in Australian Working Class History, eds. Sandra Bloodworth and Tom O’Lincoln, Melbourne, Interventions, 1998,22-3, and Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale,70.

[23] Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill, 51, 56.

[24] Kennedy, Silver, Sin, and Sixpenny Ale, 105, and Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill, 114-15.

[25] Paul Robert Adams and Erik Eklund, ‘Representing Militancy: Photographs of the Broken Hill Industrial Disputes, 1908-20’, Labour History, no. 101, November 2011,1-33, and Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’.

[26] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, Introduction, 2.

[27] BDT, 14-25 January 1916, Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 2, 15, and Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill, 199-202.

[28] Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill,203.

[29] BDT, 29 April 1916.

[30] BDT, 17, 21 March 1917, and Dale, The Industrial History of Broken Hill, 202.

[31] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 2, 15.

[32] BDT, 11 April 1916.

[33] ‘Police Reports on Political Meetings Held in Sydney Domain 1918-1921’, SRO, 7/5594, and Roper, Labor’s Titan,97.

[34] Francis Barrymore Smith, The Conscription Plebiscites in Australia, 1916-17, 4th edn. Victorian Historical Association, Melbourne, 1974,4-5.

[35] Report on ‘Labour Volunteer Army, Broken Hill’, by Detective-Sergeant Morton Gibson, ‘Unsorted papers of IWW’, SRO, 7/5588, ‘Police Reports on Political Meetings Held in Sydney Domain 1918-1921’, SRO, 7/5594, and BDT, 19 November 1917.

[36] Truth, 27 March 1921.

[37] BDT, 24 July 1916.

[38] Labor’s Volunteer Army Song Book, Broken Hill, 1916.

[39] BDT, 5,7 August 1916, 19 January 1917, Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 3, 4, and ‘IWW Papers’, SRO, 7/5590.

[40] BM, 5 August 1916, and Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 3, 4.

[41] BDT, 5 August 1916, and BM, 5 August 1916.

[42] Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale, 142.

[43] Barrier District Assembly Political Labor League (BDAPLL)/Barrier District Assembly Australian Labor Party (BDAALP), Minute Books, 19 April 1915 to 21 February 1922, OA, 90/20/30/1-4, 11 January 1917.

[44] BDT, 5 February 1917.

[45] BDT, 6 February 1917.

[46] Times, 4 June 1917.

[47] Sydney Morning Herald (SMH), 30 March 1917.

[48] BM, 7-8 May 1917, and BDT, 8 May 1917.

[49] Antony Green, ‘Sturt – 1917’. New South Wales Election Results 1856-2007. Parliament of New South Wales.

[50] Daily Telegraph (DT), 31 March – 13 April 1917, Argus, 26 April 1917, Age, 26 April 1917, and BDT, 30 April and 7 May 1917.

[51] ‘Report of Sergeant Thomas Robertson’, in ‘IWW Papers’, SRO, 7/5590.

[52] Jack Lang, I Remember, Invincible Press, Sydney, 1956, 89.

[53] J.M. Main, Conscription: The Australian Debate, 1901-1970, Cassell Australia, Melbourne, 1970, 91-92, and Reinforcements Referendum Council (1917), The Anti’s Creed.

[54] BDT, 1 April 1921.

[55] SMH, 4 Dec 1916.

[56] New South Wales Parliamentary Debates (NSWPD), vol. 79, 205.

[57] ‘Charles Reeve, Letters (17), 1919-1921, from Bathurst and Long Bay Gaols to “Mum”/ “Mother” and “Fellow Worker”’ [unidentified correspondents]’, Mitchell Library Manuscripts (MLMSS), 5653.

[58] ‘Inquiry Under the Police Inquiry Act, 1918. Report of Mr. Justice Street, the Commissioner Appointed by the Act’, 22, in New South Wales Parliamentary Papers (NSWPP, 1919), vol. 1, 26-65.

[59] NSWPD, vol. 71, 666-67.

[60] Street Commission Report, 38-39, 58-59.

[61] BDT, 23, 24 March, 8, 13 April 1920.

[62] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, ch. 2, 15.

[63] SMH, 31 July 1920, and The Socialist, 2 December 1921.

[64] BDT, 13 April 1920, and Roper, Labor’s Titan, 114.

[65] Evans, ‘Radical Departures’, 16.

[66] ‘Paul Freeman’, NAA, A1, 1921/14767.

[67] Robert Storey, letter published in BDT, 1 April 1921.

[68] ‘T D Mutch, Papers, 1907-57’, MLMSS 426, Box 8 and Box 55D. Included in these papers is a relevant article from the San Francisco Examiner, 24 April 1919.

[69] SMH, 2 June 1919.

[70] Sun, 4 June 1919, ‘Address given by Brookfield at Townsville’, and BDT, 5-6 June 1919.

[71] ‘Address given by Brookfield at Townsville’.

[72] Ibid.

[73] SMH, 4 June 1919, Truth, 27 March 1921, Peter Simonoff, ‘BrookfieldBy Peter Simonoff’, The Australian Communist, 1 April 1921, and DT, 28 August 1919.

[74] Paddy Lamb, ‘The Story of Freeman and Sergaeff, by one who knows them’, Workers’ Weekly, 30 July 1926, 4. See also Stuart Macintyre, The Reds: The Communist Party of Australia from Origins to Illegality, Allen& Unwin, Sydney, 1998, opposite 148.

[75] Simonoff, ‘Brookfield’, 1-2.

[76] Eric Fried, ‘The First Consul: Peter Simonoff and the Formation of the Australian Communist Party’, Russia and the Fifth Continent: Aspects of Russian-Australian Relations, eds. John McNair and Thomas Poole, UQP, St Lucia, 1992, 110-125, 114-15.

[77] Kevin Windle, ‘Trotskii’s Consul’: Peter Simonoff’s Account of His Years as Soviet Representative in Australia (1918–21), The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 93, no. 3, July 2015, 513. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5699/slaveasteurorev2.93.3.0493 Accessed: 31-03-2021 00:12 UTC

[78] Arthur Rae, ‘The Case of Peter Simonoff’.

[79] BDT, 20 November 1918.

[80] Rae, ‘The Case of Peter Simonoff’.

[81] Labor News, 29 March 1919, and BDT, 25 March, 5 April 1919.

[82] Report by Detective-Sergeant W.C. Duncan and Detective Sergeant John L. Pattinson, in ‘Unsorted papers of IWW’, SRO, 7/5588, BDT, 24 April 1919, 3 June 1919, 23 July 1919, J. Normington-Rawling, ‘Foundation of the Communist Party in Australia’, Quadrant, no. 37, vol. IX, no. 5 (Sept-Oct 1965), 76, and ‘Secret Seven’, in ‘Considine Michael MP’, NAA, A6119, No. 45.

[83] Kevin Windle, ‘A Troika of Agitators: Three Comintern Liaison Agents in Australia, 1920-22’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 52, no. 1, 2006, 43.

[84] BDT, 15 October 1920.

[85] Simonoff, ‘Brookfield’.

[86] BDT, 24 March, 24 May 1919.

[87] Ross, A History of the Miners’ Federation, 298.

[88] BDT, 4 November 1920.

[89] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, 191.

[90] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, 194-96.

[91] Adams, The Best Hated Man in Australia, 277-279.

[92] BDT, 17 December 1920, and Ross, A History of the Miner’s Federation, 314-15.

[93] NSWPD, vol. 80, 1814, and BDT, 2 December 1920, 12, 14, 19, 21 March 1921.

[94] Geoffrey Blainey, The Rise of Broken Hill, Macmillan, Melbourne, 1968, 125, and Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, 216.

[95] Frank Hardy, Power Without Glory, T.W. Laurie, London, 1962, 398-403.

[96] See ‘Intelligence Summary No. 18, week ending 13/9/19’. NAA, A6287/1, 18 (10 in ‘Russians’ section).

[97] ‘IWW Papers’, New South Wales State Records Office (SRO), 7/5590-3.

[98] BDT, 25 December 1918.

[99] ‘Secret Seven’.

[100] M.C. Woodhead’s statement to the Coroner’s Inquest.

[101] Argus, 5 May 1921, and Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale, 175.

[102] Wetherell, ‘Stormy Years’, 219.

[103] Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale, 175.

[104] BM, 23 March 1921.

[105] Woodhead’s statements to the Coroner’s Inquest.

[106] Kennedy, Silver, Sin and Sixpenny Ale, 175, and the Coroner’s Inquest where seven people made statements: Mounted Constable (SA) Woodhead, Constable (NSW) Kinsella, James Thomas, a railway guard; John Minns, a goods clerk; Mounted Constable (SA) Lawrence; Martin Quigley, an ambulance attendant; and Thomas Dunn, the Broken Hill municipal herdsman.

[107] BDT, 6 September 1921.