Mike Donaldson

Roy Coltman was born in Woonona and started work when he was 18 as a contract miner at South Bulli Colliery at Russell Vale in 1916. Ten years earlier a gas explosion at Bulli mine had killed Roy’s grandfather and his grandfather’s brother. Seventy-nine other men and boys died. Roy’s father narrowly escaped. After milking the family cow, Roy cycled to the pit, and then walked three or four kilometres underground from the mine entrance to the coalface to start mining, reversing the journey after his nine-hour shift ended. Roy supplied his own work gear, including explosives, and hand tools which he maintained at home. There were no washing or eating facilities or toilets at work. Rats were rife and cheeky. Roy was paid according to the tons of coal he hewed.[1] He recalled:

You were bustled all the time to make ends meet. It was all bustle, from the time you got there ‘til you went off and it was all the time. And you ran. Ran into places and stripped off and then tried to make ends meet by hewing the coal. It was terrific, the speed you had to do. Some of the miners were shoving a skip, having a leak and having a sandwich at the same time.[2]

Miners’ one-room houses at Scarborough, 1911

Source: Sydney Sun 2011

Roy was one of 3,300 miners who constituted about half the male workforce of Illawarra, whose population was about 30,000. By 1910, coal mining was already a well-established industry north of Wollongong; 16 collieries were driven into the coastal escarpment, but they provided only dangerous and uncertain employment. Five days’ work a fortnight seems to have been the norm for 1914-1919.The Health Inspector of the Bulli Shire Council reported in 1916 that “twenty-five per cent of the houses about Clifton should be condemned as insanitary and for indecency” and that there were a lot of houses belonging to mine owner Ebenezer Vickery “which really ought to have a firestick put in them”. [3] The Sydney Sun reported:

Incredible is by no means too strong a term whereby to describe the deplorable position of these unfortunate people. No one who does not know the facts would ever believe that white human beings could be compelled, in a country like this, to live as these people have to live. The dirtiest, dingiest slums of Surry Hills or Woolloomooloo cannot show such unspeakable hovels as hundreds of the Southern District colliers and their families are compelled to herd in.[4]

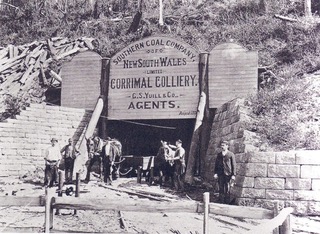

Corrimal Colliery, c.1910

Photograph provided courtesy Mike Donaldson

From the 1860s onwards there was a tradition of union militancy in most of the Illawarra mining communities. Gradually individual union Lodges at each mine came together to form the District Delegates Board in 1879. By 1916, district organisations across the country had united to form a national organisation, the Australasian Coal and Shale Employees’ Federation (generally known as the Miners’ Federation) which remained the largest union on the South Coast for more than three decades. South Coast miners’ leader, Albert Willis, became the first General Secretary of the new national union. Like many of his members, he believed that all workers should be in the One Big Union, the Workers’ Industrial Union, of which the Miners’ Federation itself would constitute the Mining Department. The Federation noted, in words borrowed from the Industrial Workers of the World:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace as long as hunger and want are found among millions of working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on until all the workers of the world organise as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production and abolish the wages system.[5]

Founded in the USA in 1905, the Industrial Workers of the World (the IWW, also known as the Wobblies) had arrived on the South Coast by 1907. J. Moroney and J. Ring addressed a large gathering from the balcony of O’Brien’s Royal Alfred Hotel on the corner of Crown and Keira Streets, Wollongong, one Saturday night in late November that year. They explained the principles of the IWW, talked of the One Big Union, and received “a very fair hearing”, according to the local newspaper.[6] Moroney said that the time was not far distant when IWW principles would be thoroughly established. Members of the organisation would visit Illawarra periodically and local branches would be set up. Meetings followed in the street near the Helensburgh post-office, and at Kembla Heights on a Saturday night in April 1912. A well-attended meeting, chaired by the President of the Mount Kembla Miners’ Lodge, listened as G. Waite and J. Batho attacked the federal Labor Government for introducing a system of compulsory military training, and strongly condemned the new Compulsory Arbitration Act.[7]

Except in Broken Hill, the Wobblies were generally itinerant labourers, swagmen, who worked mostly away from the big cities, often as miners, shearers, tree-fellers and railway construction workers (navvies). As they moved from town to town in search of work, they spread the word, using pamphlets, stickers and public meetings. The stickers were sold to activists in batches of 1,000 for 2s 6d; those with the slogans ‘fast workers die young’ and ‘someone has to be last, make sure it’s you’, were popular. Tom Barker, an IWW leader from Auckland, noted “migratory people looked for support when they came to a new place and if they found an IWW branch they knew they were amongst friends and that created a spirit of solidarity that was something more than words”.[8] But the IWW branches were hard to find. The organisation initially grew slowly to about 200 members nationally by 1913, then picked up, reaching a peak of about 4,000 in 1917, organised in about a dozen branches (although Bill Beattie, who joined the IWW in Melbourne in 1915, claimed it had a membership of 55,000, 11,000 of them financial[9]). The IWW weekly newspaper, Direct Action, which commenced publication in 1914, sold for one penny and had a circulation of about 15,000, and on occasion, 26,000.

Illawarra’s only IWW branch was set up in Woonona in December 1915; its Secretary Andy Lees, a miner at Old Bulli colliery, rented a room in the Princess Theatre to sell and display IWW and other progressive literature but had great difficulty paying the bill for the room’s one electric light. The branch planned a night class on economics and a working-class library because, as Lees put it, “the workers don’t get the right kind of reading matter: they are doped from their cradle to their graves”. Lees and visiting speakers talked One Big Union from the soap box each Sunday afternoon at the Thirroul Domain. In less than two years, the group had disbanded.[10]

Lack of finances meant that the IWW often held its meetings in the streets, empty lots, paddocks and parks, thus bringing them into conflict with the authorities. In March 1913 C. Waite, President of the United Labourers’ Society, addressed a meeting with aldermen at Wollongong Town Hall to discuss the issue. Waite said that two IWW members who had come to Wollongong to discuss the rights of the workers were sent to gaol for speaking on the street:

They were sent to gaol as evil doers. Who would say that men who expressed their opinions were evil doers? We want liberty, and more of it, but, strange to say, within the last few years our liberties had been growing less. If a man went on strike, he broke the law; if he criticised the Government, he broke the law. Instead of going forward we have been going backward. The prosecution of these men in Wollongong is more like the days of the Inquisition than of free Australia.[11]

Speaking “as a member of the Vanguard of Labour, the IWW”, he moved a resolution against prosecution for street speaking, provided there was no serious obstruction of traffic. He said that the Labor Government was a menace to liberty, masquerading in liberty’s name. “They’re digging their own grave, and we hope they will soon be in it.” H. Ostler from the Socialist Labour Party seconded his motion. Speaking in support, P. Bowling said it was well known that only socialists were prosecuted. Was it because their ideas were wrong, or because they were right? In the mines, factories and workshops, the workers were getting plundered. He mentioned cases of police making their way into miners’ meetings. They did not attend the coal proprietors’ meetings though; this was the sort of espionage that happened under a Labor government. He told the meeting that he had little more to say, except that this would not end here. The resolution was carried.[12]

The IWW has been described as anarchist, syndicalist or socialist, and may have been all three, for its members, mainly young and male, were generally more interested in drinking alcoholic beverages than in dialectics. But they firmly believed in working class solidarity and in actively fighting the capitalist class. The Labor Party was in power in NSW and federally between 1910 and 1917 but, T. Hoare and E. Rudd told a public meeting in Woonona in February 1913, it was just as bad as the conservative parties.[13] The IWW rejected parliamentary democracy and believed the state and the capitalist class could be replaced by associations of workers in control of their own industries. As Direct Action explained:

We will turn all the bosses out to work, send all the parsons to heaven, put the politicians into the zoo, and make Parliament House into a monkey-house. Then we take charge of industry, tear down the slums, turn the kids and women on to the beaches and the parks, and the whole lot of us have a damned good time.[14]

To achieve this, the IWW advocated that all workers should belong to One Big Union, and undertake direct action: strikes, the ‘go-slow’ and sabotage. Their message received a mixed response. The local paper noted that, while on the six-hour trudge westwards from Wollongong to work on the construction of the Cordeaux Dam in February 1917, “two IWWs offered pamphlets for sale entitled Sabotage: Its Relation to Unionism and How the Slow Worker Can Frustrate the Aims of the Capitalist. They were rather badly received”.[15] But it may be that the 23 full and 14 empty skips at the Corrimal Mine ‘wilfully let loose’ in October 1916 to run down the incline, causing £50 worth of damage and considerable delay, was the sort of direct action the IWW had in mind.[16]

When Australia declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, men enlisted voluntarily to fight overseas. By August 1915, as the high numbers of casualties became known at home and the war seemed unlikely to end soon, enthusiasm for it had begun to wane, particularly in small towns where supplies of willing, fit young men were soon exhausted. Many, including Daniel Mannix, the Catholic Cardinal of Melbourne, thought enough had been done already.

The Government was running out of bodies to meet its commitment of 5,500 Australian soldiers per month to the British Empire’s insatiable killing machine. Australia was the only combatant country without conscription and in mid-1915, as shiploads of the wounded and maimed began to arrive home, a plan was unfolding to introduce it. Since 1910, 16 days’ military training for all men aged 18 to 60 had been compulsory but, between 1912 and 1914, 30,000 had refused to comply with it. With recruiting campaigns not achieving their targets, Labor Prime Minister Billy Hughes called for a referendum to be held in October 1916 on the issue of conscription for overseas service.

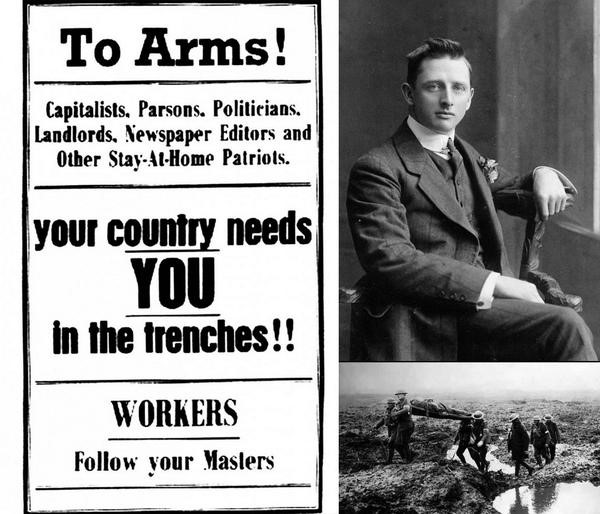

In August 1916, IWW leader Tom Barker spoke against conscription at an afternoon outdoor meeting in Campbell St, Woonona. Barker had just got out of gaol, having been sentenced to six months for publishing an anti-war and anti-conspiracy poster stating: “TO ARMS!! Capitalists, Parsons, Politicians, Landlords, Newspaper Editors, and Other Stay-at-Home Patriots. Your Country Needs You in the Trenches! Workers, Follow Your Masters!”

He had argued in his defence that it was, in fact, a serious recruitment poster. On appeal his conviction was quashed and he was released.

In his speech at Woonona, Barker said that if his treatment was a sample of justice and free speech, what were we going to get under conscription? It was only the insurrection in Ireland, he said, that had prevented conscription being introduced there, adding that Potts Point only existed today because the miners of Bulli had to work hard to provide the dividends for its upkeep. The working class would only get liberty when we could force it for ourselves.[17]

Tom Barker c.1912 (top R) with (L) the famous ‘Recruiting Poster’

Tom Glynn from the IWW moved: ‘That this meeting pledges itself to oppose all politicians who favour conscription, and, further, that immediate steps should be taken to organise a general strike if measures were taken to force conscription on them’. In speaking to it, he said that the capitalist had no sympathy for the worker. If there was a general strike, and the German Kaiser’s fleet was in the vicinity of Sydney, the capitalists would have no compunction in employing their forces to land and shoot the strikers down. Mr. Matchett, President of the local branch of the Railway Workers and General Labourers Union, seconded the motion. He said he had not intended to speak but was doing so since a report had been made about him by the Wollongong police, in which he was characterised as ‘dirty’ because he was anti-war and anti-conscription. The meeting was heated, but the resolution was carried by a substantial majority, and £2 7s 6d was collected to assist the anti-conscription cause.[18]

The anti-conscription campaign was formally launched on 23 September 1916 with a large demonstration in Sydney. Next day the police raided the IWW headquarters in Sussex St. Twelve IWW members were arrested, charged with treason and later convicted under the War Precautions Act, on spurious evidence, after several fires broke out in stores and warehouses in the city.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes forced the Unlawful Associations Act through Federal Parliament in five days, then had the IWW declared unlawful. He called the Wobblies “foul parasites” who “must be attacked with the ferocity of a Bengal tiger”. IWW members would be gaoled for a minimum of six months if they tried to impede the war effort. When two fires broke out in Coffs Harbour, the IWW was immediately blamed. It was feared they would take over Macksville and that the small towns of Kempsey and Coffs Harbour Jetty would be burnt to the ground.

Tom Barker again visited and spoke in the Coledale community hall as part of the campaign, and early in October 1916 anti-conscription activists, mainly women, disrupted a pro-conscription meeting in Helensburgh’s Centennial Hall.[19] Bob Semple, a militant miner, travelled from New Zealand to Thirroul to speak against conscription to a large meeting of miners from Coledale, South Clifton, Scarborough, Excelsior and Clifton Tunnel mines. He later became a cabinet minister in the NZ Labour Government.

While very active against conscription and against the war, the IWW was not always well regarded by some in the anti-conscription movement. On 12 October 1916 at an anti-conscription meeting in the Wollongong Town Hall (one of the largest gatherings held there for some time), Jack Sweeney, Secretary of the Illawarra Branch of the Miners’ Federation who chaired the assembly, claimed, to loud applause, that the IWW was not in any way associated with the anti-conscription movement.[20] Joseph Caddy, who was opposed to the war, was fined £6 11s in the Bega Police Court for punching William Lavington in the eye for alleging that Caddy was in the IWW. The wound required four stitches.[21]

The Easter 1916 uprising in Ireland, and the interception by the British navy of a shipment of German arms to support it, intensified fear and suspicion of anti-war and anti-conscription activists. James Connolly, a socialist trade union leader and Commandant of the Irish Citizen Army in the armed rebellion, had been a member of the IWW in the USA. “I know of no foreign enemy of Ireland except the British Government”, he wrote. Established earlier in that year, the Special Intelligence Bureau (SIB, a precursor of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation) quickly focused its efforts on the IWW, anti-conscriptionists and those of German and Irish origin. William Suscavige, a Lithuanian migrant from New Zealand, was tried in the Helensburgh Court after he had called for “three cheers for the IWW” on a miners’ march in Helensburgh. A search of his room revealed a quantity of literature, including an Irish republican pamphlet entitled Sinn Feinism and the Secret Rebellion, a copy of Direct Action and a political song sheet. He was fined for behaving in an offensive manner and for indecent language.[22] The management of Corrimal colliery dismissed all German migrant miners after their workmates refused to work with them. The South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus noted:

It would be good if the IWW could be persuaded to establish a branch, a large one, in Germany. Their deadly hostility to militarism and their militant methods would there be expending themselves upon the very root of the evil of militarism.[23]

The referendum on 28 October 1916 was narrowly defeated. The proportion of votes against conscription was substantially higher in Illawarra than nationally; nearly three quarters of the 600 who voted in Albion Park opposed conscription, an even higher percentage than in Wollongong (62 per cent opposed) and Kiama (59 per cent). The conscription issue split the Labor Party. Prime Minister Billy Hughes and NSW Premier William Holman swung to the conservatives and called a second referendum, held on 20 December 1917. The ‘No’ vote was slightly larger this second time, in Illawarra and nationally. Conscription for overseas military service had failed.

In July 1917, the Unlawful Associations Act was strengthened, making membership of the IWW illegal. Distribution of IWW propaganda and of Direct Action was also prohibited. The South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus opined:

That there are many of that unlawful association who are as sincere as can be and have the utmost courage of their convictions, is quite certain. But in a community which has the democratic principle of majority rule, there can be no excuse whatever for a party of violence. That is a means which is the negation of the democratic principle of government. And having overcome a democracy by violence, supposing IWW-ism to do so, and so become the rule, would attach to it for ever the use of violence as a means. It would be a step back into the Dark Ages.[24]

Passage of this legislation almost immediately resulted in the sacking of workers, sometimes on only a faint suspicion of IWW sympathies, the gaoling of more than 80 IWW members and the deportation of foreign-born members, of which there were quite a few. Nonetheless, the Helensburgh Miners’ Lodge passed resolutions promising support for any united action taken by the miners’ union against the introduction of conscription and urging the appointment of a government commission to inquire into the unjust conviction of the IWW Twelve. The miners also resolved to protest against the Postal Department’s ban on circulating Direct Action by post.

In the first three years of the war, the average real wage in NSW had declined 21 per cent against the rise in the cost of living. Between 1913 and 1916 there were 729 industrial disputes with more than two million working days lost, and a loss of more than £1 million in wages. Just months before the second conscription referendum and the Russian Revolution, on 2 August 1917, 5,780 workers at Sydney’s Eveleigh railway workshops and Randwick tramway workshops went on strike against what their bosses called ‘scientific management’: the introduction of timecards to record the tasks of each worker and the time it took to complete them. Like the Wobblies, the strikers resisted the ‘speed up’, calling it ‘Americanising work’ and ‘robotism’. The system attacked established work practices and unions; it intensified work, increased surveillance and created insecurity.[25] Within one week, the strikers numbered 10,000, and by the end of the second, 30,000. Two weeks later, nearly 50,000 wharf labourers, coal lumpers, coal miners, seafarers, firemen, gas workers, slaughtermen, butchers, carters, trolley and dray men and workers from the railway refreshment rooms had joined in. The Great Strike, as it is called, continued until 22 October. By this time nearly 100,000 workers in NSW and interstate were involved and 22 trade unions deregistered. The NSW Government enlisted 7,000 “loyal volunteers”, mainly from the country, to break the strike.[26] They were housed in about half a dozen camps where they were well fed, well entertained and well paid. Three thousand of them kept some of the trams and trains running. The Miners’ Federation declared its members would not travel to work on or supply coal for trains they drove.

This did not stop strike-breakers coming to Wollongong, but their stay was not pleasant. Miners and their families tin-kettled them, shouting abuse, banging on tins and pans, to and from work, the women armed with hatpins. Marching bands played ‘The Death March’ outside their homes. At Mt Kembla, a local had crossed the line. Twelve years after the strike was over, he was still abused and tin-kettled. Children born after the strike were encouraged to call him ‘scab’. He was hounded to his grave.[27]

By 6 August 1917, the miners on the South Coast had been stood down, among them Fred Lowden, a leader of the Scarborough Lodge and possibly a secret member or ex-member of the proscribed IWW. On 25 August a strike-breaking railway fireman, Alfred Green, was shot in the chest from the bush, while stoking a train’s boiler as it travelled from Wombarra to Coledale on the way to Nowra. He survived, and Fred Lowden and his friend James McEnaney, known as ‘Moscow Jack’, both Direct Action subscribers, were arrested in September for shooting him, even though Lowden had been in Sydney dining with a Labor member of the N.S.W. Parliament at the time. Police searched Lowden and McEnaney’s tiny hut four or five times, seizing and burning Lowden’s collection of books. They found cartridges matching those from the shooting wrapped in an IWW song sheet – but not on the first search.[28]

Involved in the enquiry into the wounding of Alfred Green were detectives Develin and Downey, who had investigated the killing of a police officer at Tottenham, a copper mining town in central-western NSW. On 26 September 1916, George Duncan, sole police officer in the small township, was shot twice in the back while working at his desk on the evening before his wedding. IWW members Frank Franz and brothers Herbert and Roland Kennedy were arrested for his murder. The prosecution tried hard to link the murder, Australia’s first political assassination, to the Sydney IWW Twelve. Herbert Kennedy was acquitted; Frank Franz and Roland Kennedy were hanged on 20 December at Bathurst Gaol.[29] Direct Action observed that it was a sad, mad and bad thing to murder anyone, even a policeman.[30]

It soon emerged that Charles Thorburn, well known as a police informer, on whose evidence Lowden and McEnaney had been arrested and imprisoned, had fabricated his story. Thorburn said that he made the accusation on the advice of detectives Robertson and Surridge who had been investigating the Sydney Twelve case. He told John Hughes, who revealed his deception, that he “had a quid off the police”, and was “going back to get more”, saying “this is the sweetest thousand a man ever got”.[31] Thorburn was arrested and sentenced to three years hard labour. His claims about the detectives, who denied their involvement in the frame-up of Lowden and McEnaney, were not investigated; nor was the suggestion that the sniper had come from the police or from the SIB. Who shot Alfred Green remains a mystery. Lowden and McEnaney were sacked from the mine and, unable to gain employment elsewhere, struggled to pay their legal costs.[32] Lowden eventually re-entered the industry and in the 1930s became President of the Southern District of the Miners’ Federation, a position he held for many years. Lowden Square near Wollongong railway station is named after him and for decades a large portrait of him dominated the foyer of the Italian community’s Fraternity Club, which he helped to establish in Fairy Meadow in the 1950s.

As 1917 drew closer to its end, the Kiama Independent and Shoalhaven Advertiser advised its readers of “one of the most amusing comedies Kiama folk have seen for a long time, too good to miss”. Not only was comedian Fatty Arbuckle starring in The Butcher Boy, but on the same program “will be a two-reel exclusive film showing the Great Strike from start to finish; the arrests of Kavanagh, Willis, Thompson, Buckley; the Camperdown shooting affray; the Coledale shooting; scenes at Wollongong; the raid on the IWW premises and hundreds of other interesting scenes”.[33]

By this time, the IWW organisation had been broken by the laws outlawing it, by the courts imposing them, and by the constant attention of the SIB, the police and the Censorship Board. Sergeant William Loftus of the Helensburgh police informed the Inspector General of Police in his six-monthly confidential report, “Whatever may have been implied or expressed prior to and during the [General] strike, I can safely say that from November 1917 up to the present [June 1918], IWW doctrines have been rarely discussed at Helensburgh”. Alexander Miller, manager of the North Bulli Colliery noted, “I know my colliery was at one time a hot bed of IWW’ism”, but it was no longer.[34]

But before the banning of the IWW, another revolutionary organisation, the Australian (sometimes Australasian) Socialist Party (ASP) had made a home on the South Coast.

Like the IWW, the ASP was formed in 1905, seven years before Lenin’s Bolshevik Party in Russia. Influenced by the Russian Revolution, by 1919 the ASP hoped to achieve a communist society based upon the common ownership and democratic control of the means of wealth production, wherein ‘from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs’ would be the guiding principle. Like the banned IWW, it was internationalist in its membership, orientation and outlook. Workers “have no country” but do have identical interests which are not served by imperialist schemes and wars caused by the competing capitalists of different nations.

Unlike the IWW, the ASP ran candidates for political office and engaged in other forms of parliamentary activity “wherever and whenever this activity can be used as a means of reaching the workers with its revolutionary propaganda”. However, it said, “we must not confine ourselves to mere parliamentary procedure, nor lose sight of the value of the mass action of the proletariat”. It did not endorse Labor, moderate socialist or reform candidates or policies but, like the IWW, “consistently opposes them”, aiming to develop instead “separate organs of working-class power”.[35]

The ASP did not think highly of the idea of One Big Union and rejected individual acts of sabotage, but “pledged its support to all mass industrial struggles directed by the workers against their exploiters”, in order to “sharpen the workers’ understanding of the class conflict, develop their class solidarity, and train them for the final act of emancipation”. Therefore, it declared, the “first and most essential immediate task is constant and intensive education of the workers”. Public meetings, classes and its newspaper were ways it would undertake this. The International Socialist, the Official Organ of Revolutionary Socialism in N.S.W, was first published in April 1910 and, since November 1916, by the Sydney Branch of the ASP.[36]

In April 1913, the ASP announced that it was forming a branch in Woonona,[37] and in Corrimal in November 1917 a branch formed with more than 50 members, with B. Lewis as its Secretary. General Secretary, Arthur Reardon, commented in his Annual Report to the party:

The setting up of the branch at Corrimal is undoubtedly an achievement that should have been attempted years ago. It will form an excellent base for organising the whole of the south coast mining district, and that is the ambition of the comrades in the branch. That once accomplished, the Party need have no fears as to the future.[38]

At the request of the Bulli-Woonona Anti-Conscription League, Reardon had spent five days in December speaking at public meetings in Bulli, Thirroul, Coledale, Coalcliff, Scarborough and Corrimal. He considered that “There is a goodly sprinkling of unattached rebels on the South Coast, and it is to be hoped that they will link up in the near future. It’s easy to say you’re a rebel, but it’s actual organising work that counts”.[39]

Rebels on the South Coast!

come along and link up with a scientific working-class organisation!

A welcome awaits you.

Meetings every back Sunday[40], 2 p.m.

E. R. BROWNE, Secretary, Railway Street, Corrimal.

[Advertisement, The International Socialist, 1918-1920]

By January1918, the ASP had branches not only in Corrimal, but now in Thirroul, Scarborough and Woonona (20 members), conducting weekend public meetings and classes on economics and industrial history. There were also branches in Newcastle, Coburg, Kurri Kurri and Sydney.

Thirroul and Corrimal branches, which met fortnightly, jointly organised a soap-box meeting in Wollongong, a “somewhat conservative centre”, in Reardon’s opinion. The following day, on Sunday 12 January 1919, with the help of the visiting Comrade Leece, formerly of the Social Democratic League, and Andy Lees, previously the Secretary of the Woonona Branch of the IWW, Reardon recounted “we had a splendid branch meeting. The attendance was large, and the people gave the speakers their undivided attention”. Leece lectured in the morning giving “the members a most enjoyable and instructive lesson on Marxian principles”. He spoke in the afternoon at the Thirroul monument, tracing the history of the human race to the present capitalist system, and the need for its abolition. His talk “clearly enunciated that the capitalist system is undoubtedly dead, and that it only remained for the workers to wake up and bury it to get rid of the stench. This comrade will always be listened to here”. The following weekend, despite bad weather, “well-attended” meetings were held at Woonona which “cleared up in the minds of some people any doubt as to the soundness of socialism. The principles of scientific socialism are spreading rapidly among the people, especially among the younger portion”. Sales of literature are still on the up, R.F. Sutherland reported.[41]

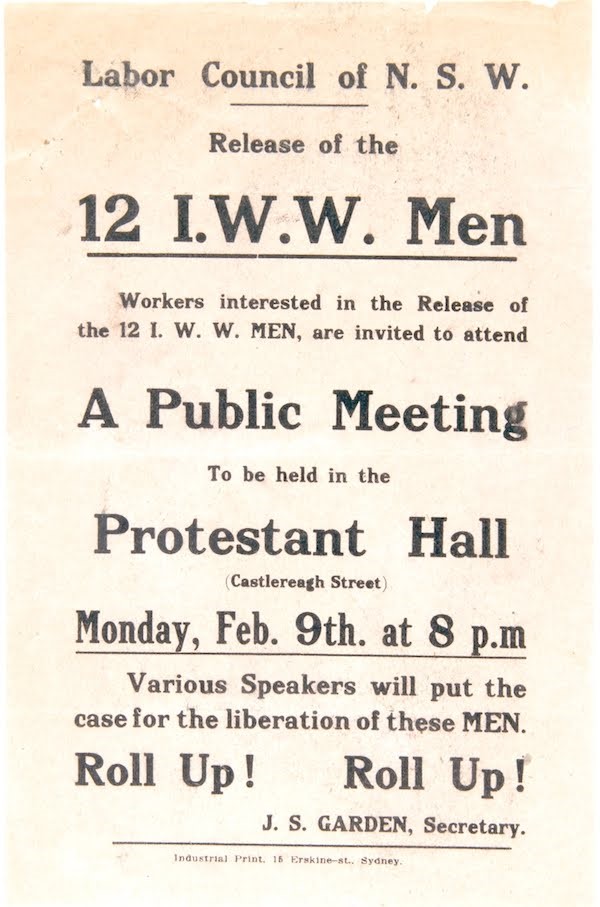

Agitation continued for the release of the framed Sydney Twelve. In 1920 Percy Brookfield, MLA, travelled from Broken Hill to speak on a Sunday afternoon in the Wollongong School of Arts Hall about ‘The plain truths about the IWW men in gaol’. “Some idea of how densely the Hall was packed will be gained from the amount of the collection taken, £9 16s” noted the local newspaper.[42] A meeting of the miners’ District Delegate Board in May resolved that it was in favour of the immediate and unconditional release of the twelve IWW men wrongfully suffering in gaol since 1916. Similar resolutions were passed at meetings of unionists at Mt Kembla and Mt Pleasant and more meetings were planned for Woonona, Wollongong, Port Kembla and Mt Keira.[43]

NSW Labor Council flyer for a meeting in support of the IWW Twelve

On winning office for Labor in April 1920, Premier John Storey immediately appointed a Royal Commission into the gaoling of The Twelve and directed the Railway Commissioner to restore jobs and seniority to 2,000 railways workers active in the General Strike. Ten of the IWW prisoners were released in August 1920, the rest slightly later. South Coast miners took the day off to help them celebrate their freedom. Shortly, a number of those released addressed a very large meeting in the Wollongong Town Hall on a Saturday night to tell of their experiences in gaol. Over £12, equivalent to about one month’s average wage, was collected in their aid. The following day, they planned to address a meeting on the beach at Thirroul.[44]

That month, the Brisbane Branch of the ASP declared itself communist. The ASP issued an invitation to a variety of socialists to a meeting in Sydney to establish a communist party in Australia. Twenty-eight people attended the gathering on Saturday 30 October 1920, which voted that ‘This Conference now form a communist party’. They elected an executive of 11 which included Arthur Reardon and two others from the ASP and Tom Glynn from the IWW, recently released from gaol and still pale of face. The ASP turned its newspaper, printing press and premises over to the new organisation.[45] That same year, a Communist Party appeared in Indonesia and in the next year or two, in New Zealand, Italy, Japan and China.

The Communist Party of Australia formed on the South Coast in October 1920 (so on the very same day as the founding meeting in Sydney, or the next, Sunday 31 October), according to Bill McDougall, a communist active in the Unemployed Workers’ Movement in the 1930s who also played a crucial role in the underground apparatus when the CPA was illegal in 1940-42. Bob Mann and miner Fred Nixon were involved in its formation, he said.[46]

The South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus noted briefly and disapprovingly on 12 November, “A Communist Party has been definitely decided upon”.[47]

Mike Donaldson is a co-author of A History of Aboriginal Illawarra and a co-editor of Comrades! Lives of Australian Communists.

Endnotes

[1] Fred Moore, Paddy Gorman and Ray Harrison, At the Coalface. The Human Face of Coal Miners and Their Communities: An Oral History of the Early Days (Sydney: Breakout Press, 1998) pp.11, 15.

[2] Moore, Gorman and Harrison, p.18.

[3] “Illawarra’s Progress”, Sydney Morning Herald, 14 August 1907, p.12.

[4] “Communities in Dirt and Dismal Places. Little Children are Taught to Pray for Happier Surrounds”, Sydney Sun, 17 January 1911, p.1.

[5] Moore, Gorman and Harrison, p.4.

[6] “Week By Week”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 23 November 1907, p.10.

[7] “Mount Kembla”, Illawarra Mercury, 26 April 1912, p.8.

[8] Drew Cottle and Rowan Day, “‘Bastards from the Bush’: Forgotten IWW Activists” (paper presented to the Conference of the Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, Canberra, 15-17 September 2011).

[9] Bill Beattie, “Memoirs of the IWW”, Labour History, no. 13 (November 1967): pp.33-39.

[10] Joseph Davis, Wobbly Wollongong, Anti-capitalist Attitudes and Activism in the Northern Illawarra’s Coastal Mining Townships of Scarborough and Coledale, 1914-1919, https://www.academia.edu/37881266/ 2016.

[11] “Freedom of Speech in Danger”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 13 March 1913, p.3.

[12] Ibid.

[13] “Week By Week”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 14 February 1913, p.8.

[14] Direct Action: Paper of the Industrial Workers of the World, March 1916.

[15] “Mount Kembla”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 2 February 1917, p.10.

[16] “Week By Week”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 27 October 1916, p.10.

[17] “Anti-conscription. Meeting at Woonona”, Illawarra Mercury, 15 August 1916, p.2.

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Helensburgh”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 27 October 1916, p.9.

[20] “Anti-conscription Meeting. Large Attendance”, Illawarra Mercury, 13 October 1916, p.7.

[21] “Bega”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 18 May 1917, p.24.

[22] Joseph Davis, Wobbly Wollongong https://www.academia.edu/37881266/

[23] “Current Jottings”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 2 November 1917, p.3.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Lucy Taksa, “Remembering and Learning from the NSW General Strike of 1917”, Hummer, vol.12, no.2, 2017, pp.15-21.

[26] Ibid.

27 Joseph Davis, Wobbly Wollongong, https://www.academia.edu/37881266/ 2016.

[28] “The Train Shooting Case”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 19 October 1917, p.19.

[29] “‘Fatty’ Arbuckle”, The Kiama Independent and Shoalhaven Advertiser, 10 October 1917, p.3.

[30] Australian Socialist Party, Australia and the World Revolution. Manifesto of the Australian Socialist Party, A Statement of Communist Principles (Sydney: Marxist Printing Works, 1919).

[31] “The Train Shooting Case”, p.19.

[32] Ibid.

[33] “‘Fatty’ Arbuckle”, p.3.

[34] Joseph Davis, Wobbly Wollongong, https://www.academia.edu/37881266/

[35] Australian Socialist Party, Australia and the World Revolution.

[36] Ibid.

[37] “New Branches”, The International Socialist, 5 April 1913, p 4.

[38] “Secretary’s Annual Report”, The International Socialist, 10 January 1920, p.2.

[39] “A.S.P.”, The International Socialist, 22 December 1917, p.4

[40] A ‘back Sunday’ was a non-pay week Sunday.

[41] “Thirroul Branch”, The International Socialist, 4 January 1919, p.2; “Thirroul”, The International Socialist, 1 February 1919, p.4.

[42] “IWW Prisoners”, Illawarra Mercury, February 22 1920, p.8.

[43] “Illawarra Miners”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 19 July 1920, p.2.

[44] “IWW Prisoners”, p.8.

[45] Bob Boughton, 2020, “Bill Earsman: 1884-1965”, in Bob Boughton et al (eds) Comrades! Lives of Australian Communists (Sydney: SEARCH Foundation, 2020) pp.6-9.

[46] Bill McDougall, “Reminiscences” – Tape Recording, B80, University of Wollongong Archives.

[47] “Current Jottings”, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, 12 November 1920, p.3.