Alexander Jordan

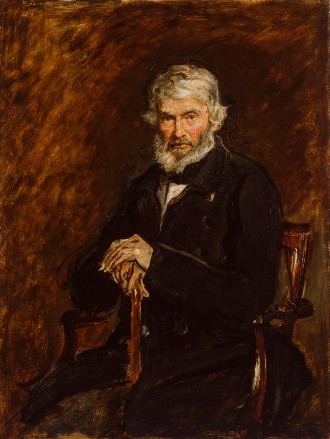

Born in the lowlands of Scotland to a working-class family, Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) renounced the Calvinist faith of his parents, subsequently coming under the influence of the German Idealists and the Saint-Simonians, a group of early French socialists. In his principal works, Carlyle preached forth the immanence of the divine in man, the infinite significance of duty, and the nobility of work, while condemning the injustices of laissez-faire and calling for an ‘Organisation of Labour’ that would guarantee work, subsistence, and dignity to the working classes.

Even the most cursory perusal of the Australasian labour press reveals that Carlyle was held in extremely high regard. For example, during the early 1890s, William Arthur Holman, the leading orator of the Australian Socialist League and subsequently a prominent Labor politician, referred to Carlyle as ‘the great master,’ praising him for having ‘written three of the finest books that had ever been penned by man.’ In 1900, the economics class of the Victorian Socialist League undertook a ‘close study of Carlyle’s Past and Present,’ while in 1903, one Queensland newspaper noted that ‘the spirit which animates and inspires the Labor Party’ was that of ‘Carlyle and Ruskin.’ During the 1920s, Peter Fraser, a native Scot and future Labour Prime Minister of New Zealand, variously referred to Carlyle as ‘one of the greatest philosophers, and even prophets, that ever lived,’ ‘a great writer who was also a great Scotsman,’ and ‘one of the greatest thinkers, philosophers, and writers who ever lived.’

As recent scholarship has emphasised, the Australasian labour movement contained a strong strain of ethical socialism, and Carlyle occupied a prominent position within this discourse. This was particularly clear in the case of Thomas Tunnecliffe, the founder of the Tocsin newspaper and the chief theorist of the Victorian Labour Federation. In a pamphlet entitled Socialism: Its Aims and Objects (1891), Tunnecliffe appealed to his readers in highly idealistic terms, invoking Carlyle’s Past and Present (1843) as an authority. He wrote:

We appeal to all who are discontented, to you who love high ideals, to you who believe in eternal truth and justice, to assist by every possible means the coming of the new order…. Let us not lose heart or waver at any obstacle, but in the words of Thomas Carlyle, let us declare, ‘That we for our share do purpose, in a full view of the enormous difficulty, to endeavour while life is in us, and to die endeavouring, till our object is attained, or we have all died and ended.’

In 1914, the NZ Truth called for unity in the Labour movement, writing: ‘Let the assembled delegates… lay to heart the exhortation of grand old Tom Carlyle: “God knows the task will be hard, but no noble task was ever easy. This task may wear away your lives, and the lives of your sons, and your grandsons; but for what purpose were lives given us?”’

Carlyle’s most important contribution to the Australasian labour movement, however, were his writings regarding the dignity and nobility of work. Particularly popular was the following section of Sartor Resartus (1833–4), in which Carlyle had written:

Two men I honour, and no third. First, the toilworn craftsman who with earth-made implement laboriously conquers the Earth, and makes her man’s… A second man I honour, and still more highly; Him who is seen toiling for the spiritually indispensable; not daily bread, but the bread of Life… These two, in all their degrees, I honour: all else is chaff and dust, which let the wind blow whither it listeth.

This passage was reprinted in the Westralian Worker, the official organ of the Western Australian labour movement, in 1904, as well as in the Collie Miner in 1911 and the Maoriland Worker in 1919.

Carlyle’s writings also supplied ideas and language through which to protest against the injustices of laissez-faire. In Past and Present, Carlyle had condemned the absurdity of crises of over-production and the mass unemployment that attended them. He exclaimed satirically:

But what will reflective readers say of a Governing Class, such as ours, addressing its Workers with an indictment of ‘Overproduction!’ … ‘Ye miscellaneous, ignoble manufacturing individuals, ye have produced too much! … Millions of shirts, and empty pairs of breeches, hang there in judgment against you. We accuse you of over-producing: you are criminally guilty of producing shirts, breeches, hats, shoes and commodities, in a frightful overabundance. And now there is a glut, and your operatives cannot be fed!’

In 1920, the Maoriland Worker reproduced this passage at length, adding: ‘Capitalism and its hacks have absolutely no reply to the conclusions of Past and Present on this point.’

Australasian labour activists also drew sustenance from the chapter of Chartism (1839) in which Carlyle had declared: ‘A man willing to work, and unable to find work, is perhaps the saddest sight that Fortune’s inequality exhibits under this sun.’ During the 1920s, these words were used repeatedly by the Scottish-born Labour MP for Wellington Central, Peter Fraser, in moving a succession of Unemployed Workers Bills. According to Fraser, although ‘many things have improved since Carlyle’s day,’ the ‘disgrace’ of forced unemployment remained.

Carlyle’s dissatisfaction with laissez-faire led him to declare epigrammatically in Past and Present: ‘This that they call “Organising of Labour” is, if well understood, the Problem of the whole Future, for all who will in future pretend to govern men.’ In 1913, Jack McCullough, a radical socialist and one of the leading trade unionists in New Zealand, told his audience:

I believe firmly with Thomas Carlyle that ‘This that they call the organising of Labour is, if well understood, the problem of the whole future for all who will in future pretend to govern men.’ To secure this, is the work that lies immediately before us… Let each of us declare, and swear if necessary, that the most essential thing to be done in New Zealand during this year 1913 is to secure unity of action. If we do this individually and unitedly, then only will we have done our duty; and hastened the prophecy of that old seer, Thomas Carlyle.

In 1914, the Australian Worker referred to the recent experience of a majority Labor government, declaring: ‘Had someone told Carlyle that the Organization of Labor would CAPTURE THE GOVERNMENT OF A WHOLE CONTINENT, and rule a territory as vast as the conquests of Alexander, the stern old sage would probably have overwhelmed him with sardonic laughter.’

Over a period of several decades, then, thinkers and activists of all persuasions found in Carlyle a valuable source of ideas, language, rhetoric, and cultural authority, particularly with regard to the ethical and moral basis of the labour cause, the nobility and dignity of labour, the injustices of laissez-faire, and the need for an organisation of labour. In this sense, Carlyle was just as crucial an influence upon the Australasian labour movement as he was upon the British I.L.P.

Dr Alexander Jordan is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg, University of Göttingen. This piece is drawn from Alexander’s article in Labour History, No. 1, 2021.

Radical Currents, Labour Histories, No. 1 Autumn 2022, 24-26.